Indoor Production

Indoors: Economics of Growing

Bags of mycelia-filled substrate are close to fruiting in Mycopolitan Mushroom Company’s subterranean grow room: a high tunnel with humidity control.

Most specialty mushrooms are best cultivated in controlled environment agriculture (CEA) scenarios. In contrast to CEA systems used for greens and herbs, mushrooms can be produced in locations with minimal infrastructure and capital to start and sustain production. Mushroom production can be adapted to abandoned and underutilized farm infrastructure including barns, outbuildings, high tunnels, and storage facilities.

In an urban environment, basements, shipping containers, and warehouse spaces can be easily retrofitted for production. This positions mushrooms to be a system that is accessible to both rural and urban farms and those farmers with limited capital for start-up.

A CEA mushroom system has several advantages, including 1) consistent temperatures (65 to 75 F) can be maintained; 2) automation and monitoring can manage relative humidity, air flow, and lighting; 3) production per square foot can be predicted and altered by modifying the climate; and 4) sanitation can be managed to reduce cross contamination and food safety risks.

As a result of these opportunities, active mushroom growers report better profit potential for indoor production as compared to outdoors. They provided estimates of $1 to $3 per square foot net income, representing a potential $43,560 to $130,680 income per acre. These values are being verified in our research, through simulated production trials at Cornell and in partnership with active growers who are collected data.

Indoor growing requires several chambers that moderate temperature, humidity, light, and air flow to maintain an environment ideal for one or more mushroom species.

The spaces used to grow mushrooms can be as small as a closet to a retrofitted room, garage, or basement, to a modified warehouse or a building specifically designed for mushroom growing.

After substrates are inoculated with spawn (see "Specialty Mushrooms" page), the material must first be incubated for the first 4 - 8 weeks in a place with consistent temperatures ideally in the 65 - 70 F range. During this stage of growth, the mycelium grows through the substrate and takes hold, drawing energy and nutrition from it.

Once this stage is complete, fruiting can occur, usually by moving the container to another space and changing temperature, humidity, light, and air flow. As the chart below shows, each species has its own needs for successful cultivating through the fruiting stage.

Five Video series on Growing Oyster Mushrooms Indoors

YouTube Link for the entire playlist: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WY8Vw0rC2Us&list=PLeB3pvIz7iiHrhVjR02W1T7_9oMBL7-B2

The most common commercial species includes Oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus), Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) , Lions Mane (Hericium spp.), Chestnut (Pholiota Adiposa), King Trumpet (Pleurotus eryngii), and Maitake (Grifola frondosa). Many grow operations start with Oyster as it offers a great range of flexibility in the materials it can be grown on and the temperature needs for incubation and fruiting.

Cultivated mushrooms are all decomposing fungi that are grown on a varying recipe typically containing a base of sawdust or wood pellets and some type of higher nitrogen supplement. When starting out, it's important to consider the local sources of materials you can obtain and experiment to determine the best mixture before scaling up.

Choosing Ready to Fruit vs Making Your Own Blocks

When thinking about growing mushrooms indoors, it is important to know that most enterprises do not do the entire process of cultivation in-house. Depending on the mission and goals of a cultivator, the involvement in each of these processes may change over time.

There is not just one way to grow mushrooms, nor the perfect place (usually) to do them. A successful grow requires that the environmental conditions are maintained to a level that is achievable and reliable, along with matching the mushroom species, strains, and substrates to perform well in this environment. The environment largely depends on the grower’s climate, location, seasonal temperature variation, and integrity of the building in terms of insulation to buffer temperature swings.

In addition to the environmental conditions, the flow of work and the tasks a grower chooses to do “in house” can have a major effect on the outcome. One of the larger junctions in the many decisions a grower needs to make is: will I produce my own blocks on site or buy them in?

The answer to this question may change over time, and it could be both. For instance, a grower might start with buying in blocks while getting a handle on production protocols. Or, one might buy in blocks to try a new species for markets or to see if their environment supports it to grow well before committing to making the blocks on site.

Before we consider the pros and cons of this important decision, let’s define what a “block” is. In the mushroom production life cycle, there are three important steps:

1) Spawn production from mushroom cultures (liquid, petri dish, live or dried specimen); this is where a culture is grown out initially on grain or sawdust. No mushrooms are produced from this material, rather it is used to inoculate other materials. Must be done with skilled techniques and in a sterile space.

2) Block production from spawn (above) that is inoculated into a mixture of substrate (sawdust, straw, coffee grounds, grain hulls, etc) with the goal of that block or bag fruiting mushrooms. These are typically done in 5 pound or 10 pound blocks - but some growers also use other containers, such as growing oysters on straw in five gallon buckets.

Blocks can either be purchased from a supplier and then put into a fruiting space

OR

Blocks can be inoculated onsite, after the substrate is cleaned of contaminants, and then incubated (for most species, 3 - 4 weeks) before being put into the fruiting space.

3) Fruiting and sales or other distribution of the mushrooms.

For more on these various sectors of the industry, read more about these industry sectors.

The focus in this article is on the block portion of production, with the assumption that the reader is considering fruiting mushrooms indoors from blocks and is considering whether to make their own blocks or buy them in.

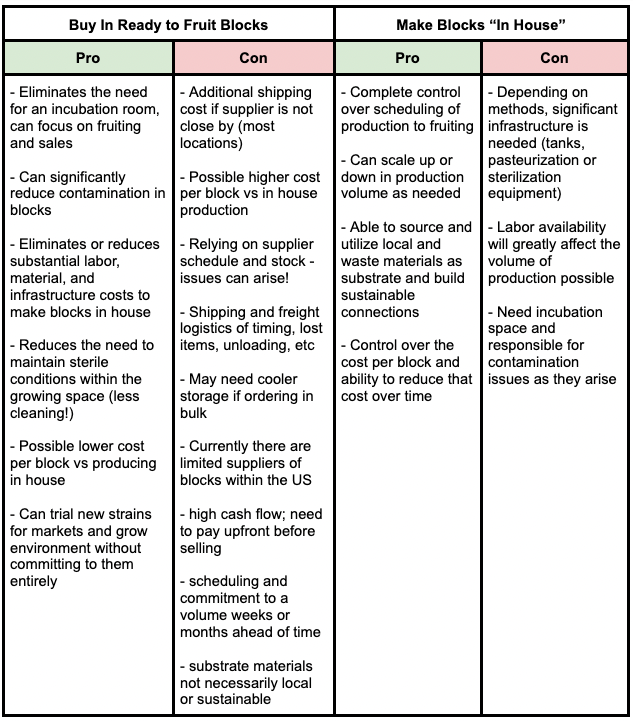

Let’s first consider some of the pros and cons of each approach, as neither is “right” in all situations but given the farm context one might be more favorable:

A summary of the above might read:

Buying in blocks reduces labor and infrastructure while increasing the need for cash flow, shipping cost and logistics, and relying on a supplier and any issues they may have.

Making your own blocks will increase labor and infrastructure costs but allow you control over substrate materials, timing, logistics, and the ability to reduce your cost per block over time.

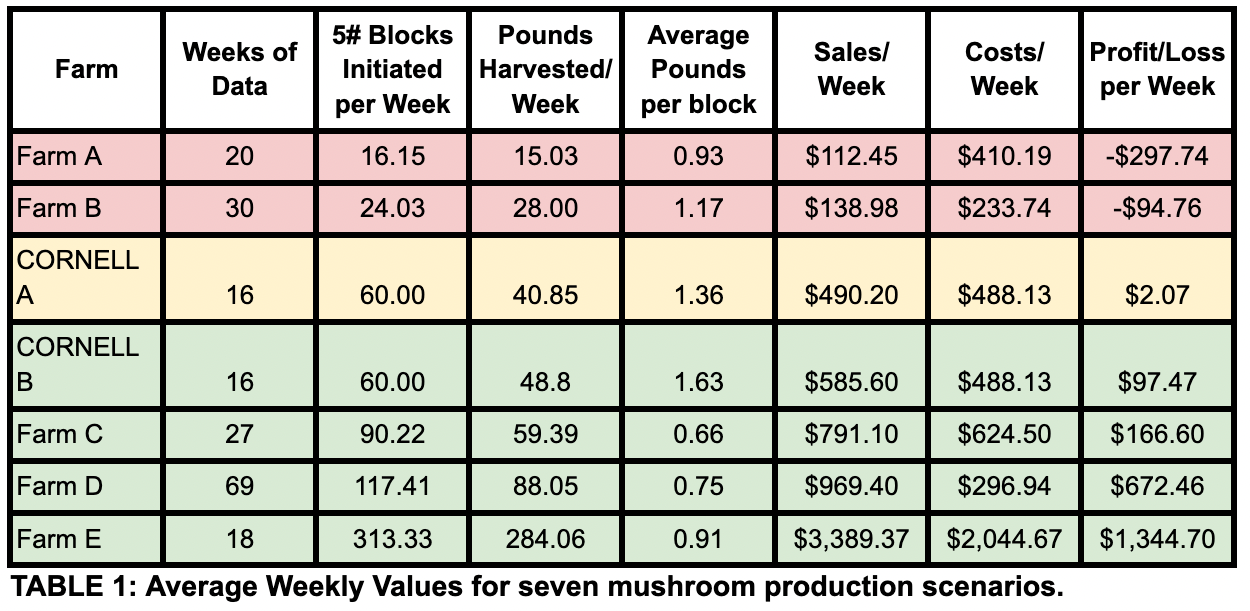

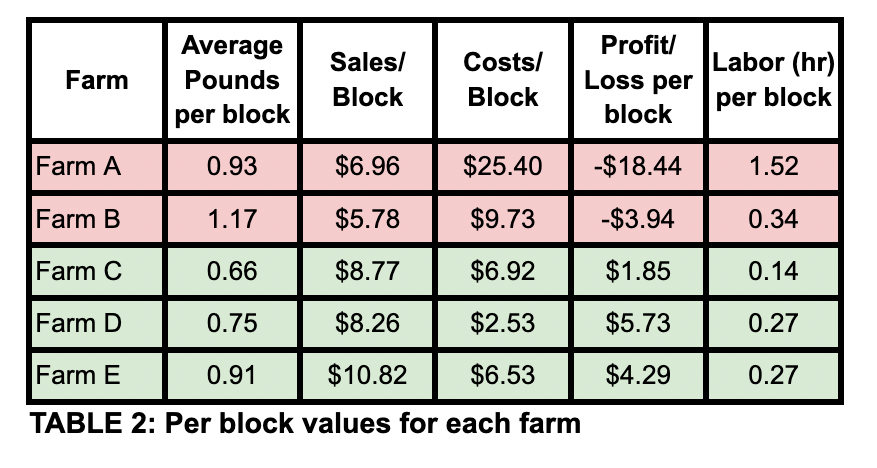

Considering these factors, let's look at grower scenarios from our research to see how these decisions can play out.

Grower Scenario Research

In 2020, we engaged potential growers along with Fungi Ally in a number of educational efforts in a grant through NE-SARE.

Growers that were ready to jump into a commercial enterprise applied for consulting support and assistance in exchange for collecting and sharing data on their production figures, sales, and labor and material costs.

This report summarizes the datasets we received from five farms as well as the Cornell block studies also conducted in 2020, which to some degree can be thought of as a “control” as a comparison to the more dynamic nature of actual on-farm production.

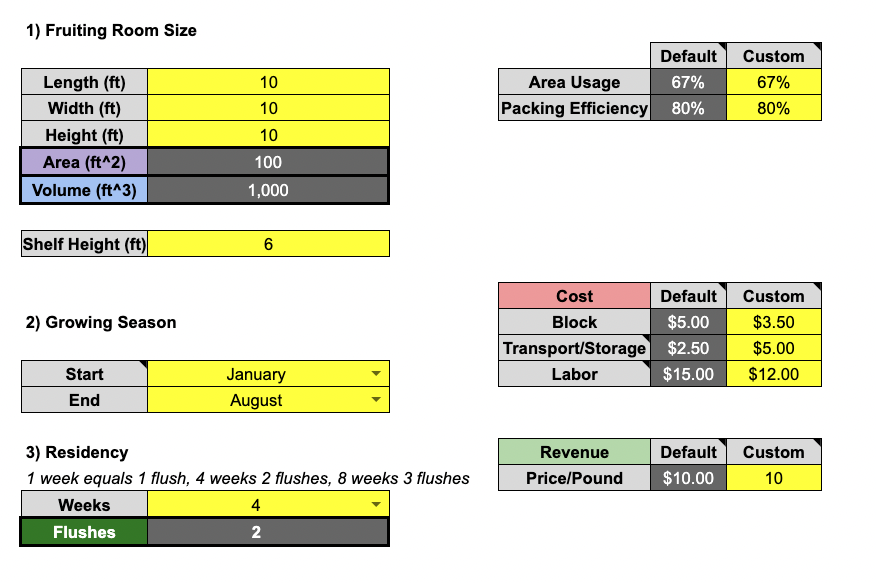

Decision Tool for Indoor Growing

When clicking on the link, you will be prompted to save a "copy" of the tool for your own use.

The "Production Specs (A)" sheet helps you walk through the decision points for your enterprise.

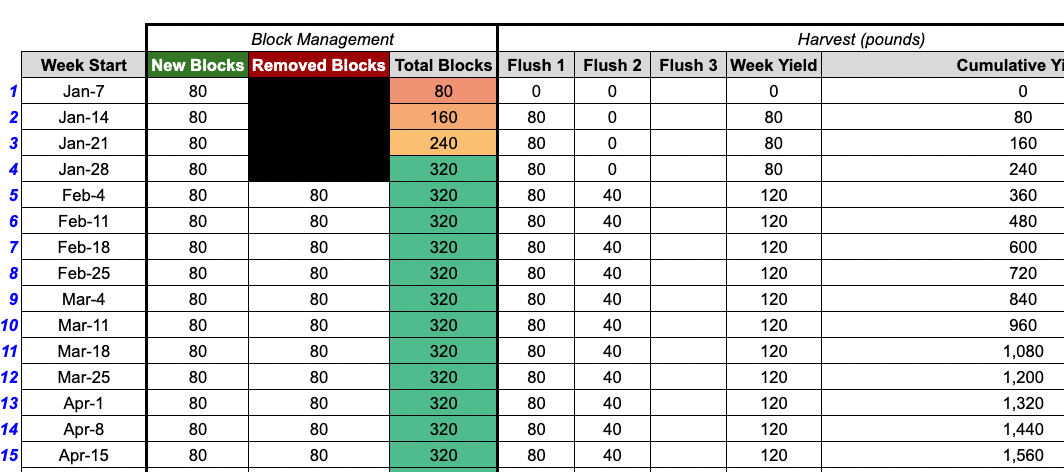

The "Projection Calculator (B)" offers a projection on production based on the parameters you choose including room size, number of weeks in production, and how long blocks are kept in production (residency) The tool

is based on just the FRUITING ROOM portion of the production cycle, and based on supplemented sawdust blocks.

If you are doing straw inoculation, the yield projections should likely be cut IN HALF as a safe estimate.

NOTE: This is a BETA version, we are currently updating it based on the grower and lab data we've collected and will be releasing a new version in February 2022.