On the Danger List: The Saga to Save the Randall Lineback Cattle Breed

If passion on the part of a few dedicated champions is the key ingredient to saving a “critically endangered” heritage cattle breed then the Randall Lineback (aka Randall) has a future. This venerable landrace breed, once common in New England, dates back to the 1600s when it likely originated from an amalgam of English, French and Dutch cattle breeds.

The statistics speak for themselves. According to the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy:

In the last fifteen years, we have lost 190 farm animal breeds worldwide. Moreover 1500 other are at risk of extinction. “In five years 60 breeds of cattle, goats, pigs, horses and poultry have become extinct.”

Five main breeds of cattle comprise almost all of the dairy herds in the United States. Holsteins comprise 83 percent of dairy cows.

Three main breeds comprise 75 percent of pigs in the US

60 percent of beef cattle come from three main breeds, Angus, Herefords or Simmental (a breed of cattle originally native to Switzerland) breeds.

Four breeds comprise 60 percent of the sheep in the US.

“Landrace” refers to a specific locale where an animal or plant has developed traits that enable them to better withstand harsh climates and diseases. The Lineback is the last survivor of the once pervasive multi-purpose farm staple used as oxen to do the heavy lifting, and it also produced milk and provided meat. According to the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, there are fewer than 200 Linebacks left in the world. In addition there are more than 200 Randalls. Despite its near extinction there are two different breed associations led by two divided factions; hence the two different names for the same animal.

The Lineback’s most recent history began in 1912 when Samuel Randall with wife and son, Everett were farming in Sunderland, Vermont. Though it is unclear how they were acquired, their animals carried the original landrace traits in that they were true to their original size and color, unlike those that had gradually been absorbed into the ubiquitous Holstein. For the next 75 years, the Randalls had a closed herd which became known as Randall Linebacks. WhenEverettdied in 1985 the Linebacks’ fortunes were bleak since many were slaughtered and the few that were left were dispersed to well meaning but eventually disinterested people.

Except for Cynthia Creech. Now the president of the Randall Cattle Registry and Breed Association, and an associate of Connecticut organic farmer, Phillip Lang, she is largely credited with saving the remnants of the Randall herd because she bought the last of the Randall family’s nine cows and six bulls. She began to rebuild the herd in the late eighties at her farm in Tennessee. She says that “there were six distinct families in the original nine girls. My herd is the only herd in the country that has the full genetic components of the entire breed. We verified this through blood and DNA testing. We knew that none of those six were immediately related.”

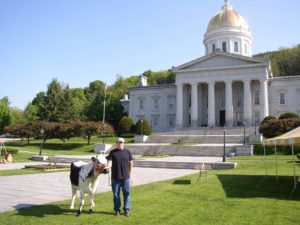

Daisy and David Randall in front of the Vermont State House on Dairy Day. In 2006, Governor Jim Douglas offcially designated the Randall Lineback a heritage breed of cattle.

In 2002 she headed north to return her herd to their natural colder New England habitat. En route she stopped at Chapel Hill Farm in Berryville,Virginia where she stayed for two years and the second chapter of the Randall comeback began. In 2000 Creech was named The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy’s “Conservationist of the Year.”

Joe Henderson, owner of Chapel Hill Farm and a man with a serious mission, is the president of the Randall Lineback Breed Association. Starting with 25 of Creech’s herd and a few others, he now has 200 Linebacks and his intention is to insure the breed’s survival by having “satellite farms around the country to keep the family lines going even if there is a devastating disease.” Henderson has been quoted as saying that when Linebacks reach a thousand in numbers, their survival will be assured.

To that end, Randall says,” when we started our breed association we all agreed artificial insemination and embryo transplant programs would play a large part. Joe has a huge semen bank and he is absolutely scrupulous about record keeping. Every breeding is taken to a science. He is keeping cow families separate and trying to get as much genetic diversity as possible.” For Henderson and his board these are the “tools for the survival of the breed.” This issue apparently is one that divides the two breed associations.

The original Randall Farm in Sunderland, Vermont where the Randall Lineback breed originated.

Though David Randall milks 140 Holsteins and Jerseys daily his passion for the Linebacks is palpable. “I would have a hundred of them. They are a perfect homestead cow, they are excellent grazers and their milk is excellent. Makes good butter and cheese. I feel like I’m milking my great grandfather’s cow.” He says “they weren’t bred for milk, more for meat and they put on weight fast.” Joe Henderson, who slaughters them at eight months, sells the Lineback beef at high prices to the “finest restaurants in theWashingtonmetro D.C. where the chefs have consistently rated Lineback meats as the finest beef out of heritage breeds.”

After an intensive two-year effort and with the help of local representatives, David Randall realized his dream to have the Lineback named as “A State Heritage Breed of Livestock.” Governor Jim Douglas signed the bill into law on March 9, 2006, the only heritage breed designation in his eight years as governor and to Randall’s knowledgeVermontis the only state to name a heritage breed of cattle.

So why all the fuss? Why have these people and others struggled so long to save this heritage breed of cattle? Clearly it is more than just a rebellion against the rise of industrial agriculture, but according to the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, it is the loss of genetic diversity. Their hardy traits allow them to live in a variety of challenging weather conditions and increase their resistance to disease. They do not need grain nor antibiotics as modern commerical breeds often do. They are important genetic resources and when they become extinct the uniqueness of their gene pool is forever lost.

Daisy in the foreground and her daughter Dolly in pasture at Kinship Farm in South Kirby, Vermont.

Cynthia Creech who now resides inDover Plains,New Yorkwith her hundred head of Randalls, says that “people are beginning to look seriously at heritage breeds because they are built for sustainable farming. They are tough. At the time that heritage breeds were being used, farming had to be responsible to the water, to the animals, to the land and to the entire environment. That’s what made it sustainable. We got away from that way of functioning so that we could produce a bigger faster product. We have discovered that it was not healthy for the land, the animal, the water, or the environment. Consequently people are looking back at what our grandfathers did.”

Farmers Bruce and Lisa Wood in Weston, Vermont, have given up most of their prized commercial herd, keeping only their six Randall cows. David remembers Everett Randall’s herd back in the early eighties and cherishes the ones he and Lisa have. “They are good grazers and they are helping us to bring back our pastures”

In the eyes of this beholder, they are simply beautiful animals.

Hello, we are a hobbie farmer in New York and we would like to breed our heifer randall lineback cow with a randall lineback bull or purchase a randall lineback bull calf to raise and breed her.

Hi there!

My husband and are starting our own small ranch and farm. We are looking for 1-2 weaned and registered Randall Lineback Heifer Calves. Can you help us get connected with someone?