Health Benefits of Grazing Dairy Heifers

A group of heifers watching over the fence at a pasture walk last summer. Studies show health benefits from raising heifers on pasture. Photo by Nancy Glazier

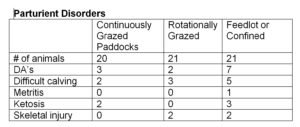

I recently completed a comparison of raising pregnant dairy replacement heifers in Confinement vs. Management Intensive Grazing (MIG). This study showed the animals raised in MIG had far fewer post partum problems than their counterparts. It was set up to compliment prior studies completed by the University of Minnesota from 2000 through 2002. Those studies showed the same advantages in health but were completed on the universities’ farm, unlike my study that was conducted with animals from two separate commercial herds in New York.

Responsibilities to be defined in a Contract Heifer Raising Agreement

Items which must be spelled out in writing include:

- How animals are identified.

- Pre-arrival treatment or conditioning required (perhaps a minimum health standard to protect other livestock at the facility, dehorned before arrival).

- Transportation in and out, who arranges, who pays.

- Age at arrival.

- Insurance coverage, who provides, what perils, how is uninsured loss dealt with.

- Age and or stage of gestation at departure.

- Growth rate expected, how defined, how monitored, penalty if not achieved.

- Heat detection, what systems are used and what is success rate, is there a plan for problem heifers (ex. Prostaglandin if not bred by x months), who pays for problem resolution.

- Insemination, what age or size at first service (Holstein example, breed first heat after 13 months, 131 cm and 360 Kg), who does, who pays, how are repeats dealt with

- Semen, who selects sire,who pays.

- Pregnancy checking, done when, who pays.

- Vaccinations, what, when, who does the work, who pays.

- Parasite control program, what, when, who does the work, who pays.

- Hoof trimming, what, when, how is need determined, who does it, who pays.

- Non-routine health care for sick animals, who does what, who pays.

- Death losses, who pays (common suggestion is if owner loses calf, feeder refunds all raising costs).

- Access to animal for other procedures such as embryo transfer (ET) work, display for sale, how arranged, notice required.

- Access by owner to view heifers and monitor program (Sunday afternoon inspections are a major time commitment and infringement on weekend privacy according to experienced custom feeders).

- Notice required for either party to terminate agreement.

- Rate of payment for custom feeding services, are arrival and departure dates included, what costs in addition to feed, bedding, utilities, labor and housing are included.

- Frequency of billing and time frame within payment is due.

- How and when can rates be adjusted or renegotiated (notice given, new rates for new animals only or all animals etc.).

- Method used to arbitrate disputes.

Other Things You Might Ask About Include:

• Who else has heifers in facility and on what terms are new clients added.

• Feed, who supplies, what quality, how tested and balanced, are there nutritional consultants used.

• Bedding, who supplies and what is used.

The goal of the project was conceived during a pasture walk on a farm in Schuyler County, NY in the summer of 2003. The group was viewing a grazing system belonging to a retired military man who contract-grazed replacements for a neighboring dairy. Some of the participants had similar operations and all participants agreed that grazing dairy replacements produced a healthier and stronger animal than comparable animals raised in confinement. The conversation affirmed there was significant opportunity to graze more replacements, especially with the dairies of more than 400 milking animals. Research was needed since there was only had anecdotal evidence when proposing the health advantages of grazing to dairy producers who were raising their replacements in confinement. I was asked by this group to find information that would help them increase their opportunity to graze dairy replacements.

A similar study from the University of Minnesota was completed by graduate student, Laura Torbert. She looked at health indicators of the animals in the two systems. Torbert’s study had shown significant differences in the postpartum health of the animals kept in grazing regimes and those kept in confinement.

These differences between the grazed animals and the confinement animals were what attracted me to duplicating the study, using large commercial dairies which would allow comparison of information gathered from herd mates. If the study showed similar results as the Minnesota study this information would aid other large dairies to see the benefit of raising heifers on pasture. Increasing the number of animals grazing in NY would have many advantages:

- Decreasing the amount of manure that feeds into a large farm’s CAFO plan.

- Creating opportunities for contract graziers.

- And finally, raising replacements that are healthier and require less medical interventions at the beginning of their first lactation.

The study used 100 heifers on two different dairy farms. The animals were taken from two large commercial herds which had a sufficient number of animals bred in the window required for the study. Each group of heifers came back to be housed and managed together on the home farm. In April 2005 the animals were selected from two farms: Farm 1 of Schuyler County and Farm 2 in Cayuga County. The 50 animals from each farm were weighed and sent to their regime within two days of each other. The grazing season was a challenging one in 2005 due to the lack of rain. The Schuyler animals had to be removed from the grazing system 30 days ahead of schedule, and a portion of the Cayuga animals came off a week early due to the lack of pasture growth. The expected result of the shortening of the grazing period was that since the animals from the two regimes spent more time together under the confinement regime there would be less of a difference between them. This was not the case. After collecting the data on post-partum problems from the two farms there was a significant difference between the health care requirements of the animals under the two regimes on both farms.

When the animals returned from pasture they were combined with the confinement group. The study was designed so that the animals would have between 30 and 60 days post treatment before calving. The heifers on both farms were selected to freshen in the period between November of 2005 and January of 2006. The calving ease was determined by the difficulty the heifer experienced delivering her calf. A score of 1 meant that there was no difficulty, 2 some assistance was necessary, and 3 meant there was exceptional difficulty. The difference between the two farms can be explained by the somewhat subjective nature of scoring. The grazing heifers needed calving treatment and had lower calving ease scores.

Torbert’s study revealed significant differences in the postpartum health of the animals kept in grazing regimes and those kept in confinement.

Both farms had similar protocol for monitoring the health of newly fresh animals. Each farm had a fresh group separate from the other cows. Each heifer had her temperature taken every day and any temperature of 102 degrees or higher for two consecutive days had an antibiotic treatment initiated. The usual cause of an elevated temperature is metritis, a vaginal infection connected to calving. Bill Stone, DVM, formerly of Cornell PRO-DAIRY, and also a collaborator on this study, commented on the increased temperature; metritis is often an indicator of sub-clinical ketosis or an energy imbalance.

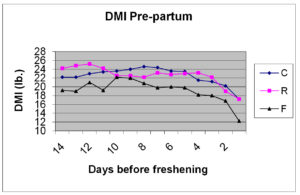

The cause of the imbalance in this case can be explained by looking at the results of Torbert’s study. On the research farm they were able to monitor dry matter intake (DMI) for each animal 2 weeks before they freshened. In the chart, Torbert showed her three regimes: Continuous grazed (C), rotationally grazed (R), and confinement (F). Note the animals that had been in either grazing regime consumed more throughout the two weeks prior to freshening, and 17 lbs DMI the day of calving. The Confinement animals dropped to 12 lbs DMI. This difference in consumption would explain the higher incidence of sub-clinical ketosis and the resulting metritis in the confined group.

Dry matter intake for each animal 2 weeks before they freshened. The three study groups were: Continuous grazed (C), rotationally grazed (R), and confinement (F).

It would be expected that lactating animals having health problems at the beginning of their lactation would show lowered milk production and longer “Days to First Breeding”. The Data collected did not show this. There was no significant difference between the two groups. A possible reason for this is the protocol for checking recently fresh animals; daily monitoring of the animal’s temperature and quick response with treatment was successful in preventing any long term effects of the ailment.

With any grazing study there needs to be multiple years of repetition since there are so many variables involved with grazing. To really understand the reasons for the differences in the two groups an in depth study should be enacted that includes; blood test, measuring of daily DM intake. Also, an economic study of the fuel and energy savings of grazing dairy replacements would help increase the use of this practice.

Information on grazing dairy replacements is now available on the Graze NY website. Posted are fact sheets on setting up grazing systems, sample contracts for owners and graziers, tips on grazing replacements, as well as this report and others. Also, I set up a Facebook page, titled “The Girls of Summer”