Tarps, Mulch, and Timing: No-Till Tools to Rob the Weed Seedbank

Research shows how the legacy of tarping and mulching can lead to fewer weeds in no–till vegetables.

By Stephen Stresow and Ryan Maher

The Woes of Weeding

One of the persistent challenges for organic vegetable farmers is managing weeds. These floral foes emerge each season from the weed seedbank–a collection of all the weed seeds in the soil. Now consider wanting to make the transition to no-till. Without tillage or herbicides, many farmers hesitate to make the leap or even risk giving it a try. Despite the challenges, a growing number of small farms are trialing new practices and finding no-till success.

Many of these farmers are utilizing tarps. Tarps can be used in many different ways, often after some form of tillage to help create a stale seedbed before planting crops. The

short-term signs of success are often visible; many of us are enchanted by seeing white thread weeds emerging from warm moist, tarped soils. We can see those weed seeds germinate, search for light, and finally succumb to the darkness in a process known as ‘fatal germination.’ Tarps can also be used to facilitate no-till systems by acting as a substitute for tillage and by killing living weeds between crops. In any case, tarps serve as a valuable placeholder on the farm, holding beds between crops and keeping weeds from gaining a foothold. The benefits of tarping can then take the form of fewer weeds in the following vegetable crop. As those successes add up, crop by crop and year by year, one question remains: how does continuous use of these no-till practices stack up to affect our weeds over time?

One way to answer that question is to measure the weed seedbank. The seedbank offers a glimpse into how effective our history of management has been at managing weeds. A large seedbank hints that weeds have been able to mature and ‘deposit’ their seeds into the soil. Management strategies that work to draw down the seedbank, have the potential to reduce the number of weeds in subsequent seasons.

To try and understand the legacy effects of no-till tarping practices, we have looked to our long-term permanent bed research experiment established at Cornell’s Thompson Vegetable Farm in Freeville, NY. In this experiment, we have managed a sequence of crops–cabbage, winter squash, lettuce, broccoli, and beets–over 8 years. Over the course of this experiment, we have compared two unique tillage systems: 1) conventional tillage with a rototiller, where soils were tilled intensively between crops and 2) a no-till system with tarping, where tarps were applied between each crop instead of tillage to prepare seed beds for planting with little to no soil disturbance. To add some complexity, and a layer of organic matter, each of these tillage systems were implemented with and without the addition of rye mulch. Mulch was applied by hand at a rate of 5-6 tons/acre to select crops over the course of the crop rotation. We have many lessons learned through this work, some still to emerge, but for the purpose of this article, we’re only going to get into the weeds about weeds! After 7 years, we set out to measure the soil seedbank of this experiment to understand the legacy effects of our management practices and learn how to best rob the seedbank of its weed-spawning abilities.

An example of weeds germinating in the greenhouse from field-collected soil. The top tray is from an untarped plot and the bottom tray is from a tarped plot. Stephen Stresow/Cornell Small Farms Program

How do you measure the weed seedbank?

We estimated the seedbank using field-collected soils that were brought into the greenhouse. Getting weeds to grow usually is not a problem, but since our goal was to flush every weed from these soils, we gave them some special treatment. For 4 months, the soil got warm, 72F temperatures, fertilized weekly, and was mixed every 4 weeks as a kind of stimulated tillage event. It also had wet/dry cycles that mimicked early spring rains. We even treated the soils to a 7-week cold stratification period to overcome seed dormancy for species that may have required it. The result was multiple flushes of weeds until the soils, weeds, (and interns) were exhausted. Each weed that emerged was identified, counted, and removed and together they gave us an interesting story.

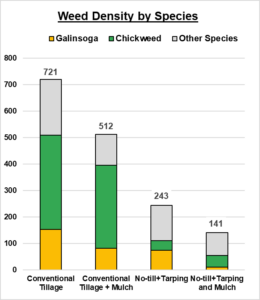

The total weed density by each soil management system. Stephen Stresow/ Cornell Small Farms Program

Which weeds did we find?

We found 15 different weed species with the two most dominant ones being hairy galinsoga (Galinsoga quadriradiata), a summer annual, and common chickweed (Stellaria media), a winter annual. Many vegetable farmers in the Northeast cite galinsoga as their most problematic weed species, responsible for yield losses of 10 to 50%. This is partially due to galinsoga having no seed dormancy, being able to set seed as soon as 35 days after emergence, and producing multiple generations in a single season. Chickweed, too, can create about four generations per year and can reroot from cuttings in moist conditions. We’ve been managing these soils for years so the prevalence of these two weeds was not too surprising, it was how many and where they showed up that was more insightful. Neither of these species has seeds that survive for more than a couple of years in the soil, which means that if you can keep them from setting seed you can start to see reductions in their populations. Understanding weed traits is important for developing management strategies that target specific weeds. For life cycle descriptions of your common weeds and strategies to manage them on the farm, look to the comprehensive new SARE publication, “Manage Weeds on Your Farm: A Guide to Ecological Strategies.”

In our experiment, when it was time to plant in the spring, chickweed (and other winter annuals) were already well-established in bare soil and required multiple tillage events to kill. Stephen Stresow/Cornell Small Farms Program

No-Till, Tarping Triumphs

We found that no-till with tarping had 66 to 80% fewer weeds than conventionally tilled soils.

In our trial, tarps were most often applied in the early spring or overwinter. When applied during this timeframe, tarps are poised to reduce winter annual weeds, like chickweed. At the beginning of planting season, chickweed is already firmly established in untarped plots. These “shoulder season” tarps covered the soil when winter annuals were actively establishing, preventing them from getting their footing and maturing to set seed. Tarps may have also reduced chickweed through ‘fatal germination’, as soils begin to warm in the beginning of the season. This early season weed control can give crops a competitive advantage over weeds, leading to further reductions in weed populations.

Mulches Make Do

Mulched soils had on average, 30 to 40% fewer weeds than plots without mulch .

Using mulch in a tilled system reduced galinsoga by 46%. No-till with tarping, with or without mulch, had about 90% less galinsoga than the

conventionally tilled soils. The no-till with tarping and mulch system had an average of just 10 galinsoga plants per m-2, compared to 153 in conventional tillage without mulch! We think these results were largely due to the fact that mulches have weed-suppressing power throughout the growing season when summer annual weeds like galinsoga are expected to emerge. For example, we found that galinsoga thrived in winter squash years, and tarping alone was not enough to maintain season-long weed suppression. In the later years of our experiment, we started using tarps in the summer between spring-planted lettuce and fall plantings of broccoli, which could be another strategy to break up summer annual weed life cycles.

Three weeks after transplanting broccoli in our experiment, no-till with tarping

plots (right) had lower early-season weed emergence than conventionally tilled, untarped plots (left). Stephen Stresow/ Cornell Small Farms Program

Our results show that both tarps and mulch have their role in drawing down the weed seedbank by combining multiple tactics that target

different species. Reducing the seedbank takes time and vigilance! One year of many weed escapes can set weed management efforts back many years, hence the adage “one-year seeding, seven years weeding.” Regardless of the weed management strategy employed, sustained efforts to reduce the seedbank can have benefits for years to come.

To learn more about tarping and ways to implement this practice on your farm, visit the Reduced Tillage project page at www.smallfarms.cornell.edu/projects/reduced-tillage/

Ryan Maher’s work began with the Cornell Small Farms Program in the summer of 2013 and focuses onresearch and extension in soil health practices for vegetables.