To Tarp, to Mulch or to Do Both: That Was the Question

CSA Farm experiments to minimize inputs, mechanization and soil disturbance in their market-scale potato growing operation.

By Bob Tuori, Ryan Maher, and Michael Salzl

A major concern on our highly intensive organic farm is how to grow potatoes on a scale that supplies our diverse and abundant CSA shares yet in way that minimizes labor needs and detrimental effects on soil health. We grow on a limited space (hence, the farm name) and so have largely relied on rented, off-farm fallow fields for potato growing, leaving the highly fertile and carefully managed on-farm land for specialty crops. Managing these fields in a minimal yet sufficient manner is complicated by their abundant weed seed bank and the added burden of transporting equipment. Weeds in potato fields that are minimally managed can be so aggressive as to completely crowd out the slow emerging vines. Even if the vines initially outcompete weeds, the field can become overrun with weeds by the time the vines senesce, complicating harvest. Hay mulch is an inexpensive local input and provides a soil cover, reduces weed germination, maintains soil moisture and adds organic matter to a field. Tarps, while a pricey upfront investment (we paid $500 for two 32×100 silage tarps), can be used for multiple years. The basis for our experiment was to see which method to use, or how to combine them, to improve our success with reduced tillage potato production.

Reduced or no-till farming has gained much attention in recent years, due to the potential for increased soil health and reduced labor inputs. Tarping has also emerged as an accessible and versatile tool for small farmers to overcome some of the common challenges to reducing tillage, including weed suppression and cover crop termination. However, farmers continue to look for examples of how to best fit tarps into specific windows in their crop rotation. Of growing interest, is how tarps can be successfully integrated with other soil building practices, like cover crops and mulches, to provide both short and long-term benefits.

We designed this experiment to trial tarping as a method to improve cover crop termination, weed suppression, marketable crop yields and labor use. We compared three growing methods: tarping with mulching (T+M), tarping without mulching (T), and no tarping with mulching (M; this was our standard practice). For each method, potatoes were planted into a tilled strip following an over-wintered cereal rye cover crop.

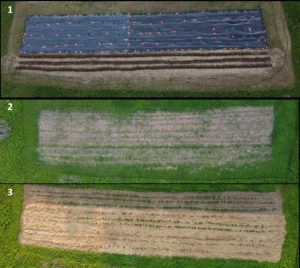

(Figure 1) Drone photos showing the field from tarp to mulch.

On June 2, just before the tarp was removed and potatoes planted. The furrows on the bottom of the photo are in the M-only treatment and were built that day.

On June 24, potato plants are just beginning to emerge, one-week prior cultivation and mulching.

On July 5, shortly after cultivation and application of hay mulch. Tarp-only treatment on top has only rye residue on the soil surface.

Image provided

What we did:

We started with an old hay field that had no history of vegetable production. In the fall before the potato year, the field was mowed close to the ground, a cereal rye cover crop was broadcast by hand, and the entire field covered with ~3 in of hay. Field preparation for planting potatoes started on May 3rd for tarped treatments (T and T+M), about 3-4 weeks prior to our target potato planting date. At this date, the rye was between 6-12” tall. Before tarping, we made planting furrows about 12” wide, 6’ apart, using a BCS tractor with a rotary plow attachment. The rye between these tilled strips was left undisturbed. We then applied tarps directly over both the furrows and untilled rye. They were secured with plenty of sandbags, left in place for 4 weeks, then removed just prior to planting (June 2nd) (Figure 1). The rye cover on the non-tarped, mulched treatment (M) was allowed to grow during the month of May and then flail-mowed and furrowed on the same day as planting. We planted 3 different varieties in each treatment, one row each with an early (Pontiac Red), mid (Keuka Gold,) and late-season (Red Maria) variety. Seed potato was placed in each furrow and covered with hoes. The potatoes emerged within a few weeks and on June 30th, about one month after planting, we cultivated both sides of the planting row to loosen soil for hilling (~2 inch deep, 30 inch wide) using a BCS tiller with precision-depth control. The potatoes were hand-hilled with hoes and then mulch was applied by hand (~6-8” deep hay) to the two mulched treatments (T+M and M; Figure 2).

(Figure 2) Field immediately after the tarp was removed (6/2). Tarped (right, dark colored rye) and non-tarped treatments (left) compared side by side. Seed potatoes are being placed in tilled strips and covering with hand hoes. Image provided

Prior to mulching, we measured weed emergence and rye regrowth to assess the effectiveness of the tarp in rye termination and suppression of early season weeds. We also measured weeds and rye regrowth later in the season, close to potato harvest, to assess the role of tarping and mulching in longer term weed suppression. We monitored soil temperature and moisture throughout the season and sampled for soil nitrate in the planted furrow to see how tarps affected crop-available soil nitrogen. Starting in September, before the vines had completely senesced, we began hand harvesting. At this time, we also sampled the field for soil health using several of the Cornell Soil Health Test metrics (active C, soil respiration and protein levels). All tubers were washed and then sorted as either marketable, greened or vole-chewed.

What we found:

Some of our results were unsurprising and largely driven by the field and weather conditions rather than our treatments. Soil moisture was not different and consistently high, so not a limiting factor. The summer was very wet, but in dry years we would expect the mulch to provide added benefits. Soil health tests showed equally high measurements across the field, which could be expected for a fallow field.

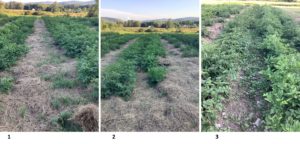

(Figure 3) Ground cover in each of the three treatments on August 3. 1) Mulch only, 2) Tarp + Mulch, 3) Tarp-only. Note rye regrowth in 1 and the mat of small weeds in 3. Image provided

We found tarping effectively terminated the rye cover crop. Very little rye was found growing in either of the tarped treatments (T and T+M) while it regrew in the non-tarped and mulched treatment (M) so that by midsummer it covered ~1/3 of the area and was the most important weed. While mowing can kill rye when the rye is at full flowering, or anthesis, timing and logistics for this can be tricky and our rye stand was not quite there. However, when compared to mulching, tarping alone did not provide comparable full season weed suppression. Throughout July and August weed pressure remained minimal, especially in the tilled planting row (Figure 3), but by the end of September, the perennial weed situation had become extreme in the non-mulched tarped treatment. Weeds covered 73% of the area between potato rows in this treatment, versus 45% in M and 28% in T+M treatments. It’s not clear how much these weeds affected potato crop growth as the vines had nearly completely senesced at this point, but they did make the harvest more cumbersome. It was clear that tarps alone were inadequate for suppressing our perennial weeds and these weeds are likely to return as problems in future years. Tarping in conjunction with mulching seemed to have a synergistic effect by combining to reduce rye regrowth and provide longer lasting weed suppression throughout the season.

One of the most notable results of our study was the increase in nitrate levels in tarped versus non-tarped soils (4 ppm pre-tarping baseline, 4.5 ppm M-only, 17 ppm T+M and 15 ppm T-only). Tarping could have increased soil nitrate at planting by killing rye early and thus eliminating soil nitrogen uptake by the cover crop while creating warm, moist soil conditions that promote biological activity prior to planting. Our analysis of soil temperatures indicated that both daily maximum and minimums under tarps were consistently 2-5 degrees higher during the tarping period and returned to baseline within a week after the tarp was removed.

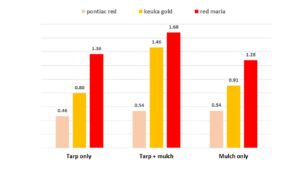

The overall marketable yield was highest in the T+M treatment (736 lb.) versus 524 lb. and 544 in the M and T treatment, respectively. The marketable yield of two of the varieties (Keuka Gold and Red Maria) accounted for this discrepancy. Yield per row foot for each variety and each treatment is shown in Figure 4. Pontiac Red was poor-quality seed, with low germination and equally low yields in all treatments. We expect that in a dry year, the yield difference between mulched and non-mulched plots would have been even more significant. We suspect that the higher nitrate related to tarping, combined with added weed suppression provided by the mulch helped account for the increased yield of T+M treatment.

All labor hours directly involved in production were carefully tracked throughout our study and used to calculate a ratio of yield versus labor hours invested. This analysis allowed for some helpful insights. Applying and removing the tarping required significant labor and tarping alone was not worth the labor investment. Tarping with mulching had the greatest yields but also required the most labor. Mulching without tarping did not demand as much labor but also did not yield as high. Therefore, we found the yield to labor returns to be nearly equal between the M and T+M approaches (T-only, 13; T+M, 17; and M-only, 17, all in lbs./labor hr). With practice, we have found that applying and moving a tarp becomes easier and we feel more confident about preventing the tarp from blowing away. This may reduce labor in future operations. Clearly, mulching seems to be indispensable for reduced tillage potato growing on our scale and it is relatively inexpensive. Adding tarping seems to improve yield, add some labor efficiency, and gives us more confidence and flexibility in killing cereal rye in spring without tillage.

We plan to continue to refine this method. One big adjustment will be to prepare the planting furrows after tarping the cover crop rather than before. Making the furrows prior to tarping added some logistical headaches: uneven ground made it difficult to walk and move sandbags without creating holes in the tarp. Laying the tarp directly over cover crop (with no furrows) would allow it to sit more tightly against the surface, resulting in higher soil temperatures and potentially improving suppression of rye and weeds. Tilling furrows after tarping could “wake up” new weeds but we feel confident that hilling and mulching will take care of that. Both tarping and mulching practices have their benefits that can add up – that’s why our answer is both.

Learn more about using tarping in vegetable production on the Cornell Small Farms Reduced Tillage Project website.