Pasture Soil Compaction: A Slow, but Stealthy Thief of Pasture Productivity

Soil compaction by grazing animals leads to loss of pore space, which can have tangible impacts on pasture productivity.

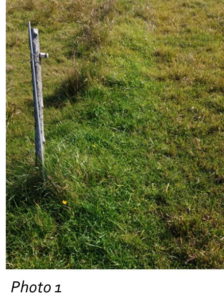

Photo 1 : Under the fence line, I could see the soil under the fence was a good six inches higher than the pasture soil.

I had a pasture soil compaction epiphany while working in a St. Lawrence County pasture on a NE SARE-supported project. The project was to plant radishes and other brassicas into established pasture swards. The goal was to try methods of establishment of late-season forages which would increase the palatability and nutrient density of fall pastures. The project had only minimal success because even though I burned back the pasture sward with acetic acid, it eventually grew back and smothered the young brassicas. While standing in the pasture, I looked under the fence line (see photo 1) and could see the soil under the fence was a good six inches higher than the pasture soil. Under closer inspection, the plants under the fence were a healthier mix of cool-season grasses, while out in the pasture there were clumps of sedge grasses, which is an indication of low oxygen in the soil due to compaction. The other interesting piece of information was that I was in the pasture with the farmer who had managed it for the past 15 years and he had not noticed the difference in soil heights. I believe that this was because compaction happens very slowly over the years and goes unnoticed. Once I became aware of this phenomenon, I began to see it in more and more pastures that I visited. But how big of a problem was it?

Photo 2: Pathways for water infiltration is also impacted by “Platy” structures forming in the upper layers of soil.

It made sense to me that pastures would have some compaction, after all, animals that graze these pastures are out every day in the grazing season, even in times of heavy rainfall which is when soil is most prone to hoof compaction. When putting together a proposal to NE SARE to investigate pasture compaction, I found studies that showed a medium-sized cow could have more compaction per square inch than a medium-sized tractor. To get an idea of what happens to soil when compacted, see diagram 1 showing the pie charts comparing compacted soil vs uncompacted soil. In the uncompacted soil, the area in a defined volume of soil is evenly divided between pore space and the minerals that make up the soil. In compacted soil, the pore space is reduced by about half so that there is a higher percentage of minerals in the same space. This loss of pore space has far-reaching effects on the soil to be productive.

Loss of Pore Space Reduces Pasture Productivity

Air space is the most affected by compaction. Its loss affects three components of productivity:

- The beneficial biology in soil is aerobic, therefore it needs oxygen to breathe, as well as space to exhale carbon dioxide. The biology is responsible for breaking down organic matter and converting it to microbial metabolites which enter roots to feed pasture plants.

- Lack of air space in soil limits deep-rooted pasture plants and encourages plants, such as sedge grasses, which survive in soil with low levels of oxygen by using an air tube. This is part of its anatomy that brings air from above ground to its roots below ground. I saw this firsthand at the pasture in St. Lawrence County, as well as others.

- Limiting the environment for biology to do its work, reduces the strength of soil aggregates, which speeds up compaction.

The reduction of pore space for water in the soil also has negative impacts on productivity:

- Reduction of the water holding capacity of the soil will decrease sward growth in times of drought.

- If there is less water in soil aggregates in the spring, the compaction relieving action of “frost heaving” will be reduced since there is less ice to expand in the aggregates.

- Water infiltration will be reduced to lower portions of the soil since pathways will be impeded to handle rainfall. This, in turn, causes ponding on the surface which only exacerbates the issue of compaction. If the pasture is located on a hillside, the ponding turns into the runoff of nutrients.

- Pathways for water infiltration is also impacted by “Platy” structures forming in the upper layers of soil. (see photo 2) The plates are formed by hoof compaction in upper levels of the soil. The plates can be seen by digging a shallow test pit and looking for horizontal lines in the soil which can be separated easily by a knife or by hand. In severely impacted soil, roots can be seen growing horizontally, rather than vertically, along the plates. The forming of plates in pasture soil impacts roots to lower levels as well as water infiltration.

Other outcomes of the NE SARE study of pasture soil compaction

A fact sheet prepared by myself, Nancy Glazier, and Abbie Teeter was accepted by NE SARE to help farmers, not only identify, but remediate pasture soil compaction.

In our work, we are researching a method for comparing penetrometer readings from one year to the next. This would allow a farmer or researcher to measure any changes in pasture soil compaction due to changes in management from one year to the next. A single reading of soil resistance with a penetrometer will vary from one day to the next due to soil moisture changes. Our hypothesis is that by taking two readings in the pasture, one from the optimum compaction area under the fence line and one from an impacted area in the pasture, the ratio of the two will remain constant since whatever variable impacts one area will have the same impact on the other area. We are calling the comparison of these two sites the Pasture Compaction Ratio (PCR). The ratio of the two areas will hopefully capture any changes in the pasture compaction since the fence line reading will always be optimum the only changes will be due to changes in the pasture soil resistance.

Our work will continue into 2021, when we will have three years of data collected on the PCR.

Compaction in pastures is difficult to avoid because of the need to have animals on them in all types of weather. Basic management tools to reduce and prevent compaction are:

- Keep your soil organic matter high, because it is related to aggregate strength which allows soil to be much more resilient when it comes to compaction. This can be done by grazing more mature grasses and following the “graze half and leave half” rule. This puts the carbon back into the soil.

- In times of heavy rain try to stay off pasture soil that is prone to compaction, such as silty soils or fields prone to flooding.

- Switch from grazing to haying on paddocks that allow it. Haying a paddock allows deeper roots to increase the oxygenated zones of your soil.

Watching the health of animals on pasture is enjoyable and easy to do, observing the health of pasture plants or the sward of a pasture requires a closer look and some specific knowledge about plant identification. To observe the health of any soil, including pasture soil, is an evolving field of knowledge. Graziers can add to this knowledge by observing and bringing their observations to extension and research personnel. After all, as Paul Harvey said, “Despite all our accomplishments, we owe our existence to a six-inch layer of topsoil and the fact it rains.”

More information can be found online.

This article also appears on the South Central NY Dairy & Field Crops Team blog