Building Healthy Pasture Soils

The following article is an excerpt from the factsheet “Building Healthy Pasture Soils” available in full at www.ATTRA.org and can be downloaded as a free PDF at the website, along with many other guides and resources.

Let’s consider the agricultural practices that help build healthy soil. In essence, we want to increase aggregation, contribute soil organic matter, increase biodiversity, buffer soil temperature, and minimize soil compaction and disturbance. Sounds like a lot, right? Well, not really, if we break them down into six basic principles. Let’s take a quick look at the principles that will define our soil management practices for grazing:

Minimizing tillage preserves soil structure, encourages aggregation, and keeps soil carbon in the soil profile where it belongs. Tillage brings a flush of oxygen into the soil that spurs microbes into a feeding frenzy on carbon molecules, resulting in CO2 release. We reduce tillage through the use of perennial pasture and minimum or no-till of cover crops.

Maintaining living roots in the soil for as much of the year as possible feeds soil microorganisms all year. Also, by maintaining living roots and leaving grazing residual, we are covering the soil all year, forming an “armor” to protect it from loss of moisture and nutrients.

Maintaining species diversity is achieved with cover crop mixes and the use of diverse perennial-pasture mixes. Try to incorporate warm-season and cool-season plants, both grasses and broadleaf plants, in the same fields.

Managed grazing can be good for the land, the soil, and for livestock productivity. Source: Jeff Vanuga and courtesy of USDA/NRCS

Managing grazing is accomplished by planning for an appropriate grazing-recovery period on your paddocks, keeping in mind that plants need various recovery periods depending on the species, the time of year, and the soil moisture content. Overgrazing (not allowing adequate recovery) reduces root mass, photosynthesis, and the amount of carbon sequestered into the soil, decreasing soil life. Proper grazing builds soil.

Finally, utilizing animal impact and grazing impact provides nutrient cycling in pastures, and contributes to soil organic matter. Additionally, the grazing action on forage plants encourages root growth and root exudation of plant sugars that feed soil microorganisms.

For livestock producers, this boils down to a combination of perennial pasture, cover crops in rotation on annual fields, and good grazing management. These simple concepts are described by ranchers Allen Williams, Gabe Brown, and Neil Dennis in a short video on how grazing management and cover crops can regenerate soils. View the video Soil Carbon Cowboys to get their take on soil health practices.

Grazing Dynamics

Perennial pastures, because of the lack of soil disturbance and their permanent cover, are higher in carbon and organic matter than tilled crop fields. This biological system has a stable habitat to conduct business, and the nutrient cycles can sustain themselves. However, we know that by adding livestock to the mix, we get a multiplier effect on soil health.

The impact of grazing is known to increase soil carbon and nitrogen stocks. As an animal grazes, it sends a signal to the plant to pump out sugars through its roots and into the surrounding soil, or rhizosphere. Root exudates, which are sugars developed by the plant through photosynthesis, are food sources for myriad microorganisms in the soil. The action of grazing jump-starts the soil food web and increases nutrient cycling, making nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon available to the growing plants.

Walt Davis, a rancher and management consultant, puts it this way: “Grazed forage pumps root exudates (mostly carbohydrates) out into the area around their feeder roots; this feast of sugars and starches brings about an explosion of bacteria which causes the populations of predator microbes to increase greatly. As the predators consume the bacteria, they take in more protein than they need and excrete the excess nitrogen (in a plant usable form) out right where the plant that contributed the carbohydrates can grab it to produce new growth. All of this activity (the life and death of billions of organisms) plus the root growth of properly grazed forage swards creates the fertile and biological active top soil that is the real solution to sustainable, productive and profitable agriculture.”

How to Manage Grazing in Two Easy Steps

There’s a lot of information available about rotational grazing, multi-paddock grazing, and controlled grazing… it has a lot of names. As well, many graziers will extol the benefits of rotating animals from paddock to paddock. Paddock rotation is a management practice that helps us control grazing and has been shown to increase the sustainability of grazing operations. A system that rotates livestock through paddocks can be reduced to two essential steps:

First, determine how long your rest, or plant recovery period, should be. Then, determine how long animals should be on a paddock. Everything else in paddock rotations stems from these two decisions.

Recovery period

Recovery period is the number of days that animals are not on a paddock, when the forage has a chance to recover from grazing. A rule of thumb is to start the spring with fast rotations, say moving livestock every 15 to 20 days, and increasing the recovery period as it gets warmer and drier, to 30 days or so for cool-season grasses and 40 or more for warm-season grasses. These figures are for improved pasture in the Northeast, so a bit of judgement and adaptation for your region is crucial here.

Grazing period

Once you know your recovery period, determine how long animals will be on the paddock. The animals should be removed from a paddock before grazed forages begin to regrow, to prevent overgrazing. For most forages in rain-fed pastures, this is around two to three days. Grazing periods of a day or less, especially with high animal density, provide uniform grazing and efficient manure distribution. High stock density builds soil.

It’s important to maintain an adequate post-grazing residual forage height for photosynthesis and the recovery of carbon and nitrogen stocks. Remember that severe defoliation decreases car- bon and nitrogen over time. A good grazing pol- icy is to take half and leave half. This feeds both our livestock and soil microbes, resulting in less added fertilizers.

Remember: Managed grazing with adequate residual heights encourages soil aggregation, which is compromised with poorly stocked grazing. Situations that result in compaction should be avoided, such as grazing wet soils. Paddock grazing periods that are too long result in overgrazing. This is especially detrimental when the grazed paddock is not allowed full recovery before re-grazing.

Paddock Size and Grazing Uniformity

As mentioned before, livestock grazing contributes to nutrient cycling and increases soil organic matter. Managed grazing allows for uniformity of paddock defoliation but also encourages uniformity of manure distribution within the paddock.

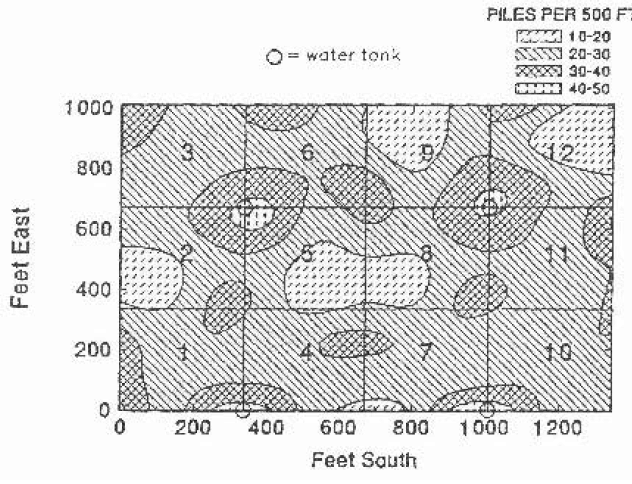

Let’s take a look at three different paddock systems and the influence that number of paddocks has on manure distribution. In the three-paddock system in Figure 2, it’s easy to see that the cattle congregate around the trees and the water source. Most likely, this system has long grazing periods, which increases grazing selectivity. It also clearly decreases uniformity of grazing. Spatial distribution of manure can be managed in many ways: for instance by the size and shape of the paddock, the placement of water sources, and the number of animals on the paddock. Paddock size should be determined by an assessment of the forage demand of the livestock and the forage available in the pasture. This will also determine the number of paddocks you need in a grazing cell.

Lesson 3 of the ATTRA Managed Grazing tutorial covers this concept, and I recommend reviewing the principles to determine paddock size and number. The ATTRA Grazing Planning Manual and Workbook: A Toolbox and Template for Writing a Practical Grazing Plan provides worksheets and a calculator to help you determine paddock size and number

Square paddocks work best for encouraging uniform grazing and, thus, uniform manure distribution. Some practitioners suggest that long, narrow paddocks don’t work very well because livestock will graze one end of the paddock more intensely than the other. However, some have noted that with high stock density, livestock will graze a rectangle-shaped (or really any other shape) paddock just fine, working from one end to the other. The key here is animal numbers, as well as the length of time they are on the paddock. Long, rectangular paddocks can work if animal numbers are high and the grazing period is very short, creating a very high stocking density.

Another way to encourage even grazing distribution is with water-source placement. Water should be placed within 300 feet of the farthest reaches of the paddock for best distribution, but still, manure tends to accumulate toward the water source, especially as the temperature increases. Research has shown that, during heat stress, most dung accumulates within 100 feet of the water source. Shade and extra water sources can help alleviate this problem.

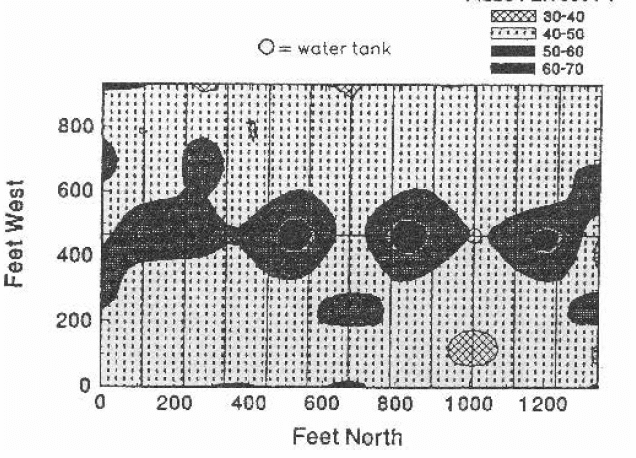

The 12-paddock system in Figure 3 is a little better. Notice that a higher number of manure piles is distributed around the paddocks. Finally, in the 24-paddock system in Figure 4, we see even more piles distributed throughout the paddock, even if there tends to be a high amount around watering sources. Compare this system with the three-paddock system. The more paddocks you have, the better the distribution of manure over the whole pasture.

Water tank placement, short grazing periods with high animal density, and more paddocks can maximize grazing distribution. In a well-designed pasture system, like the 24-paddock system, animals will deposit about 85% of their manure and urine within the paddocks, about 12% around water sources, and the rest in the lanes and, for dairies, the parlor.

Transitioning to a biological system from a chemical system is going to be a slow process, and it’s good to

recognize that it will take several years for soils to start turning around. Be patient and, as Ray Archuleta, a conservationist with NRCS, says, “you cannot build ecology integrity without human integrity” (2017).

Have the integrity to believe that nature will work with you over time; that it’s going to work.

I like to know more

This article provides valuable insights into the principles of building healthy pasture soils. I appreciate the emphasis on minimizing tillage maintaining living roots and managing grazing to promote soil health and biodiversity.

Professional HVAC Services in Chandler