A Dark Cloud Looms Over Farmland

Farm Succession Planning in Vermont Shines Light for a New Generation of Farmers

“I want to die with my boots on,” a New England farmer stated in a focus group held by the American Farmland Trust and Land For Good, to study U.S. Census of Agriculture data on retiring farmers and future plans for the farms.

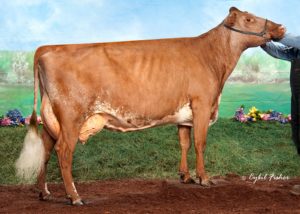

Green Acres Milking Shorthorns cows were sold as a part of a successful farm transfer in Randolph, Vermont. Credit Green Acres Milking Shorthorns.

According to the study in April 2016, nearly 30% of New England’s farmers will most likely retire during the next decade, and only one in 10 are farming with someone age 45 or younger by their side. This paints a grim picture surrounding the future of farming and accessibility of farmland to the next generation of farmers for food production in New England.

“Some senior farmers may have a plan for their farm’s future,” said Jesse Robertson-DuBois, New England Director for American Farmland Trust. “But we learned through this study that many do not. A large number of older farmers are worried about their ability to retire and to find a younger farmer who can afford to buy their land.”At no point is a farm’s future more at risk than during ownership transition. Farmers involved in the study expressed they need help to make sound transfer agreements.

“The 1.4 million acres they [farmers] manage and $6.45 billion in land and agricultural infrastructure they own will change hands in one way or another,” said Cris Coffin, Policy Director for Land For Good, who directed the study. “To keep this land and infrastructure in farming as it transitions, we will need better policy tools and increased support services to exiting and entering farmers.”

Aires Hill Family Farm: The Atherton Thompson Family transferred Aires Hill Family Farm between generations. Credit Aires Hill Family Farm.

Farm Transition Stories from Vermont

Joan Wortman is a senior farmer who had been looking to retire from milking 100 cows at her family farm, Green Acres Milking Shorthorns, in Randolph, Vermont.

“Lots of today’s farmers are middle aged, getting into their late 50’s and 60’s as I am, and having family to take on the farm is such a rare thing now. There aren’t as many young people who want to follow in their parent’s footsteps,” Wortman shared as she was making final preparations to sell her cows at auction in May.

The auction took place four years after Wortman began working with the Vermont Land Trust’s Farmland Access Program to find a younger farm family to take over the farm. Farm succession planning takes time, and Wortman found it was challenging to find people who fit the criteria of what she was looking for so Green Acres would remain a small family dairy farm.

The diligence of the Vermont Land Trust paid off and Wortman sold the farm to a young family from Pennsylvania, originally from Vermont and looking to come home. The new owners are bringing their own herd to Vermont, leaving Wortman to put her cows up for sale—an emotional experience, but one she knew was the last step in transitioning the farm.

“My cows have been part of the family—it’s like putting all of your kids up for adoption,” she shared. “But it’s the best thing ever to have a program that can help young farmers connect to farmers looking to retire. I don’t know where I would be now without the Vermont Land Trust—it’s been a big relief!”

While the number of dairy farms may be shrinking that have family able to take over the farm, programs like the University of Vermont Extension’s Family Farm Succession are helping Vermont farm families successfully transition within the family. Aires Hill Farm worked with UVM Extension so Karie Thompson Atherton, age 35, could take over the day-to-day operations of the 7th generation family dairy farm in Berkshire, Vermont. Atherton has been running the farm since 2014, which consists of 500+ acres, 220 milking cows and 150 young stock.

In a recent interview, Atherton very clearly articulated some suggestions to New England farmers in family transition situations:

Importance of Farm Succession Planning: It’s important to get both generations to the table and, at the very least, start a discussion. There is no “correct” way to start the succession planning. Every farm and every farmer is different. There are so many unknowns it’s important to see where everyone involved stands and not make assumptions. Your ideas may be closer than you think, or further from what you could ever imagine possible. It’s a very difficult and complicated process and it will take many years to accomplish. It’s never too early to start planning. You think you have time and then someone’s health deteriorates and you’re in panic mode. That is not ideal. It adds a lot of stress to a situation that is already stressful.

Sources for More Information:

American Farmland Trust

Land For Good

UVM Family Farm Succession

Vermont Farm to Plate

Vermont Land Link

Vermont Land Trust

Challenging Conversations: Talking about transitioning the farm is very challenging and in my case involved several family members. We never talked about transitions over the years, and lots of assumptions were made. Those assumptions can be the death of a family, and I cannot stress how important it is to communicate. When you start talking about the farm, all of its heritage, and how much blood, sweat, tears, and sacrifices that have been made to get the farm to where it is today, it can get really personal and emotional. Modern technology can be a double edged sword and divide the generations and it’s important for everyone to be heard.

Making the First Step: Start talking the sooner the better—it’s in everyone’s best interest—both farming and non-farming family members. Just because some of the family doesn’t actively work on the farm doesn’t mean they don’t care what happens to the farm. To start, both generations need to identify the goals for the farm and take small steps to change. It doesn’t mean the younger generation has to farm “the way Dad did” forever, but it will be a huge help to get through the process in the early stages and earn each other’s respect before making new changes. All parties involved should be able to have both financial and personal needs taken into the planning process.

Aires Hill Family Farm: Maggie Atherton, an 8th generation future Vermont dairy farmer. Credit Aires Hill Family Farm.

Suggestions for Farmers to Get Transitions Started: Start the conversation. Listen, be respectful. Find someone you trust to guide you. Sometimes bringing in the most educated, experienced person isn’t the right choice. Your local accountant, lawyer, or financial adviser that you have worked with for years and knows your farm, your family, and your specific situation may be the best person to help navigate the transition. The younger generation needs to be aware of the financials and have access to the books. Farming is a tough way of life and it’s hard to make ends meet sometimes. Everyone needs to be fully aware of the whole picture, as it may be a rude awakening for younger family members who may not have been involved. It is better to know early on if a farm transition is feasible to remain in the family.

In Vermont, organizations including the Vermont Land Trust, UVM Extension, and Land For Good are working together as a part of the Farm to Plate Network with many other non-profits, farms and businesses, government agencies, and institutions to implement Vermont’s ten-year (2011-2020) Farm to Plate Strategic Plan to strengthen the food system. Protecting and expanding environmentally sustainable farmland in agricultural production is one of the priorities of the Farm to Plate Network in the next five years. Access to affordable farmland is imperative to increase our local food supply and grow our agricultural economy.