Nitrogen Cycling in Pastures

Follow nitrogen as it moves its way around a pasture.

I was recently asked about the copious amounts of white clover in a pasture as the farmers were concerned about bloat risk with their sheep. She and her family had done some research and came up with differing opinions regarding management. I was asked to give the definitive answer. We talked through some scenarios and came to a manageable conclusion for their operation. I did some research of my own and provided some suggestions. What intrigued me was around nutrient cycling, particularly nitrogen, and how we take it for granted and make assumptions.

This photo shows an excellent amount of legumes in the pasture. Photo by Nancy Glazier.

Pasture systems are complex cycles of nutrients. This article will focus on nitrogen (N), the most-limiting nutrient for pasture production. Other macro- and micronutrients are needed for N uptake, but due to space it all can’t be addressed in this article. Adequate N supports forage growth or dry matter (DM) production. Nitrogen also affects protein content of the grass. Adequate nitrogen helps provides nice, green, color to pastures and will provide quality forage for milk, meat, and fiber production.

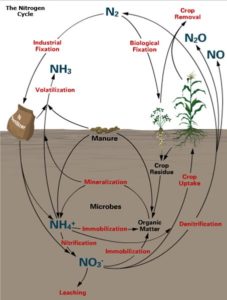

Plants take up N via their root systems in the form of nitrates and ammonia. This can come from nitrogen fertilizers and mineralization (decomposition) of manure and organic matter. Soil bacteria do the work using carbon as energy and nitrogen to facilitate growth and reproduction. Mineralization rate is dependent on soil temperature, moisture and aeration, and also on the amount of microbes present.Legumes are included in pasture mixes because, through their symbiotic association with nodule-forming Rhizobium bacteria, they fix N from the air. They are high-quality forages with common ones in Northeast pastures are red and white clovers, alfalfa, and birdsfoot trefoil.

Nitrogen is present in air at 78%, but only legumes can make use of it. Healthy nodules are either white or pink. These are the little bumps on the roots. For the most part, N fixed by legumes isn’t directly available to grasses, though small quantities can be transferred between plants through the hyphae of symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi connecting their root systems. This may provide 20-40% of their fixed N to grasses during the growing season (Brophy, 1986).

The cattle have grazed this pasture, but there is still adequate residual pasture left to capture returning nutrients and encourage new growth. Photo by Nancy Glazier.

In order for legumes to fix N, they need to be planted with inoculum. These bacteria are species-specific and need to be fresh. They can be planted without being inoculated, but will not fix as much or almost no N, especially if legumes have not been grown there for a while. Legumes fix varying amounts of N through the year. Generally, alfalfa is the highest ‘fixer’, followed by white clover, red clover, and trefoil. This amount varies by the age and health of the legumes.

To become available, organic N in legume plant tissues must first be broken down to plant-available mineral forms by animal digestion or by decomposition in the soil. When livestock have access to legume-grass pastures, they will eat and trample what’s there. They will leave their feces and urine on the pasture. Ideally, livestock are on the paddock for a short duration and uniformly distribute manure. Adequate residual pasture will help capture the urine to reduce volatilization. Plants, including legumes will readily use the ammonia; this will slow fixation due to the availability of highly-soluble N.

This is a representation of nitrogen cycling. (Agronomy Factsheet 2: Nitrogen Cycle, http://nmsp.cals.cornell.edu/publications/factsheets/factsheet2.pdf)

Nitrogen can be lost to the atmosphere. Denitrification occurs when soil conditions are wet or anaerobic (lacking air) bacteria will transform nitrate into atmospheric N. This reduces N availability of the plants. Ammonia may be converted to atmospheric N, too. This is called volatilization and occurs when temperatures are high and ammonia is exposed to the air. This can be reduced if manure (urine) or ammonia fertilizers are incorporated.

Nitrates are not held tightly in the soil. Rain or snow melt has the potential to leach or move the nitrate further down in the soil layer and out of reach of roots. There is a higher risk for leaching with sandy and cold soils. There is more nitrate N uptake when plants are actively growing, which reduces leaching risk.

This article provides a brief overview of cycling processes in pastures. Legumes can provide adequate nitrogen if the soils are active and healthy. The publication, Nutrient Cycling in Pastures by Barbara Bellows, is an excellent resource that takes an in-depth look at good pasture practices that foster effective use and recycling of nutrients. It provides basic descriptions of water, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous cycles in pastures. It can be downloaded here.

Nancy Glazier is Small Farms Specialist for the NWNY Dairy, Livestock & Field Crops Team, Cornell Cooperative Extension. Her office is in Penn Yan and she can be reached at 585.315.7746 or nig3@cornell.edu.