Lion's Mane: A new candidate for profitable forest mushroom cultivation

by Ken Mudge

Forest cultivation of shiitake mushrooms has become one of the most important non- timber forest crops in the Northeast. Well-established methods of cultivation, along with strong market demand for log cultivated shiitake, have made it a fairly reliable crop for experienced as well as beginning forest farmers. Yet, Shiitake is only one of a number of specialty forest mushrooms with potential for small-scale commercial cultivation. One that I’ve been working with for several years at Cornell is an exciting and exotic addition to any woodlot; the Lion’s Mane mushroom (Hericium erinaceus, H. americanum).

Forest farming is an agroforestry practice in which high value non-timber forest crops are cultivated in the unique microclimate created by an existing forest canopy (Farming the Woods, Mudge and Gabriel 2014). Forest farming is not only a way to produce mushrooms and other forest products in an ecologically sustainable way, it also brings economic diversity and additional incomes to rural areas, as well as encouraging responsible forest management.

According to the USDA National Agricultural Statistical Service, in 2012–2013 specialty mushroom growers produced over 8.9 million kg of mushrooms in the United States (indoor and outdoor). Although there are good opportunities for forest cultivation, most commercial cultivation of specialty mushrooms is indoors, which is energy and resource intensive, involving processed substrates (sawdust, chopped straw, etc.) and climate-controlled growing facilities.

On the other hand, forest farming of specialty mushrooms involves less intensive outdoor cultivation on unprocessed logs. While there is a significant amount of log-based forest production of shiitake (Gold et al. 2008), outdoor production of other specialty mushrooms including lion’s mane is extremely limited, but are an attractive opportunity for future development. This has been a focus of research at Cornell’s Arnot forest over the past 7 years.

Figure 1: Ericium erinacous fruiting on beech totems at Cornell Research Sites. Photo by Steve Gabriel

Lion’s mane (Hericium species) are common saprophytic (decomposing) fungi found on decaying trees throughout the Northern United States and Canada. There are three species of Hericium that are found in Eastern North America. They are Hericum erinaceus, H. americanum, and H. coralloides. All members of the genus produce more or less globoid white fruiting bodies (atypical mushrooms) covered in downward cascading spines. In addition to being edible these mushrooms have been shown to have medicinal properties (Abdulla et al. 2008) making them a prime candidate for the specialty mushroom market. The taste of lions mane is highly desired by chefs and is said to resemble lobster and seafood. There is currently a limited commercial market for H. erinaceus (pom pom mushroom) produced indoors on sawdust substrate, but practically no forest (log) production.

Just as increasing consumer interest in specialty mushrooms has motivated the development of improved shiitake strains (clones) that are better adapted to consumer preference, seasonal constraints, and other quality and production considerations it is reasonable to expect that strain selection and improvement will result in improvements in lion’s mane cultivation. Currently there are very few strains of lion’s mane commercially available. The long term goal of research was to evaluate the totem log production system for growing lion’s mane and to assess the possible usefulness of lion’s mane as a non-timber forest crop capable of income generation for small scale forest farms, either as a complement or an alternative to shiitake mushrooms.

In 2008, Jeanne Grace initiated this experiment as part of her Master’s degree research and the original totems inoculated in 2008 have been monitored for mushroom production each year until 2013. Her experiment was designed to compare the performance of four different strains of Hericium sp. using a totem production system. Fungal strains are clones, analogous to plant varieties. Each strain is initiated from a single mushroom propagated vegetatively on a substrate like sawdust. A strain can be repeatedly propagated for many generations.

In addition to the question of strain selection (different genotypes) on yield of lion’s mane mushrooms, which has obvious commercial implications, several other considerations were also addressed by this research including the post inoculation delay (years) before mushroom production begins, the proportion (percent) of inoculated totems that actually fruit, the duration (years) of mushroom production from a totem, and the seasonality (within year) of mushroom production.

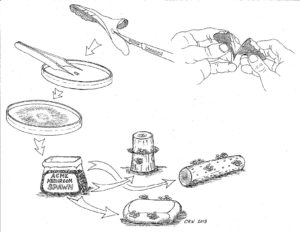

This study compared 4 different strains – one Hericium erinaceus from a commercial source designated FFP3, and 3 strains of H. americanum (He 3, He 4, and He 5) collected locally (upstate NY) and isolated in a our laboratory. The process of strain selection from a wild mushroom, involves isolation on a petri plate followed by spawn production on sawdust, and finally inoculation and eventual fruiting is shown in Figure 3.

About 30 totem stacks of American beech for each strain were inoculated with sawdust spawn. and mushroom production was monitored for 5 years. Not all stacks produced mushrooms (fruited) during each of the 5 growing seasons. The percentage of stacks that fruited for each strain was noted for each year. Table 1 shows that the percentage of stacks that fruited varied from year to year.

All three of the strains except FFP3 fruited at least once over 5 years. Seven of xx stacks of FFP3 did not fruit at all over the course of the experiment. Interestingly, a stack that did not fruit was not necessarily “dead” since most of the non-fruiting stacks during any given year, fruited during some or all of the subsequent years.

This finding, that totems from different strains do not have an equal probability of fruiting, has implication for any future commercial production because of the considerable time and labor involved in cutting down trees, transporting logs to the laying yard, and construction and inoculating the totems. The lower the probability (percent in Table 1) of fruiting of totems inoculated with a given strain the more trees must be cut and transported, and more time and effort must go into totem construction.

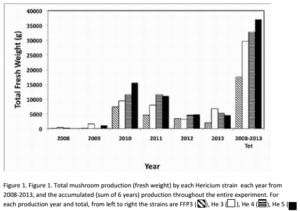

For example, the time and effort required to achieve that same level of production for the FFP3 strain (60% fruiting) would be considerable greater than for He 4 (80% fruiting) (Table 1), even though the two did not differ significantly with respect to yield of mushrooms. In contrast, well-managed shiitake logs typically have approximately 95% fruiting (Mudge et al, 2013). Figure 1 shows the harvested yield (pounds) for each strain for each year.

The apparent differences yield among the strains was not enough to be considered statistically significant (i.e. the variation among strains could be accounted for by chance alone). On the other hand, year-to-year differences among strains was highly significant. During the first two years (2008-2009) mushroom production was low, but fruited in earnest during the third and fourth years. Production declined significantly during the last two years.

These differences in mushroom yield among strains and the number of years after inoculation are important considerations for anyone hoping to grow lion’s mane in order to make a profit. Since there are no economic or marketing data available for forest cultivation of Hericium, and since shiitake is currently the only economically viable forest cultivated mushroom, a limited comparison between the two is warranted.

To begin with, the grower will have to wait for two years after inoculation before fruiting commences, rather than just one year in the case of shiitake. Our results suggest that yield during any given year may not differ very much among strains, although this tentative conclusion is based on only 4 strains. Yield of lion’s mane is another key consideration. How does yield of lion’s mane compare to that of shiitake? Shiitake yield varies from grower to grower, and there is very little published information about this.

As we reported earlier in the SFQ (Winter 2015), researchers from Cornell, University of Vermont, and Chatham University undertook a 3-year SARE project Mudge et al. (2013). They worked with 13 beginner shiitake farmers and monitored production expenses and incomes for 100 newly inoculated logs. They found that after two years the average yield of shiitake mushrooms necessary to economically “breakeven” (income = expenses), was about 0.4lbs per log. By comparison, the yield of Hericium mushrooms, (as shown in Figure 1) for peak production years 2010 and 2011 was in most cases substantially greater than or equal to the 0.4 pounds per log per year threshold for established for shiitake.

Although there was no significant difference among the four lion’s mane strains with respect to the yield of mushroom per log, yield varied significantly depending on the number of years after inoculation, with peak production during the third and fourth years. Peak production levels were similar to the commercial yield of forest cultivated shiitake mushrooms. The successful forest production of Hericium mushrooms on totem stacks, and the yield potential demonstrated here suggest that this non-timber forest crop may be suitable for commercial production.

What we currently recommend to growers looking for commercial viability is to build a business and markets based on shiitake, which can be fruited more reliably. Then, additional gourmet mushrooms such as lions mane will be easily sold to pre-existing outlets, a form of “icing on the cake” for the aspiring forest farmer.

Ken Mudge is emeritus professor of Horticulture who devoted many years of his career to research and development of forest grown mushrooms, bringing their status from a hobby crop to one that has commercial viability. He recently co-authored a book, Farming the Woods with SFQ editor and colleague Steve Gabriel.

Visit www.cornellmushrooms.org to learn how to inoculate a wide range of mushrooms in your woodlot.

I’m from Northern Alabama and I would like to grow Lion Manes at home. Can you recommend the types of trees that I could use for growing this mushroom. I want trees that are indigenous to the Southeast area.

Thanks

PS. I also interest in Morel Mushroom

Joe, if you are just getting started, I would recommend buying the inoculated sawdust blocks. You will have good luck with them and give you time to do more research.

Two years ago, I inoculated a 4″ high Oak tree stump and several fresh cut logs with Lion’s Mane substrate. Non have fruited to this date; 9/2017. Is there still a chance for them? I was going to start fresh. The stump seems to be mostly covered with something like Turkey Tail.

Thanks,

Rick

Hi Rick,

I would suggest contacting our agroforestry expert, Steve Gabriel, with your question, as he has a lot of experience with Lion’s Mane cultivation – he can be reached at sfg53@cornell.edu. Thanks!

There Is no chance for your lion’s mane. If it was going to work it would have worked much sooner than that.

If Turkey Tail is growing on the stump it’s too late to grow any mushroom.

I’m interested lions mane mushroom cultivation

Please guide me..

Hi Mata,

I’d suggest looking at the two tutorial videos produced by Cornell’s agroforestry department. An introduction to growing mushrooms (such as Lions Mane) totem-style can be found here, and an overview of Lions Mane’s colonization and fruiting patterns can be found here . Additionally, cornellmushrooms.org has a variety of helpful resources, including how-to guides, information on mushroom markets, and notices for upcoming mushroom classes. Hope this helps, and good luck!

Which tree’s in the Boreal forest are best to get Hericium Erinaceus from? In Northern Canada we have different tree’s.

Hi Steven,

I did some research and it looks like Sugar Maple would be your best bet. Oak varieties are also supposed to work well, as well as Black Walnut and American Beech. Hope this helps!

None of those trees grow in Canada’s boreal. Your best bet would be a poplar either Populus tremuloides/grandidentata/balsimefera . Its not the ideal species for lion’s mane inoculation though. You can try hericium corraloides on conifers. I have seen them grow on conifers in rainforests in BC, not sure how they would do on conifers from the boreal though.

Hello. I recently (about 6 weeks ago) prepared 2 four foot freshly cut oak logs, about 14″ diameter. I cut them into totems, put them on cardboard at the base, put spawn (H. Er.) on all the slices, and covered it with a black plastic bag, securing it with bungee cords. Yesterday, I pulled the bags off and was delighted to see white mycelium everywhere, including the top and even where bark had fallen off. I replaced the plastic bags with some used burlap sacks and secured them. Hopefully this is a good idea, to let the mycelium breathe. Should I also cover the burlap sacks with plastic? Are burlap sacks too porous? How long should I leave the sacks on for? A year? And after the year is up, remove the sacks permanently except for winter? Thank you. I haven’t seen much writeup on those steps. Cheers!

Hi, I forwarded your question to the authors of the article!

-Kelsie

Hi everyone. I’m a mushroom researcher in the Philippines. I’m currently working on the cultivation of Hericium spp. using agro-based substrate. It took 2 months for the mycelia to fully colonize the bag. I’m hoping they will successfully grow as I open the bags later.

This seems like a good place find Lion’s mane info. I have several very very technical questions to ask and would like to do so privately with an experienced researcher if possible possible.

Thanks

Ken

Hi Ken,

A good starting place for your questions is the Cornell Mushroom Cultivation website: http://blogs.cornell.edu/mushrooms/

If you aren’t able to find the answers to your questions, there is contact information for researchers on the site. Good luck!

Please correct my poor spelling missing words or extras and poor grammar. Thank You Ken

I have access to large quantities of coffee grounds that have been brewed and filtered with some nitrogen added. I would love to grow lions mane mushrooms using this as a substrate. Your advice would be greatly appreciated

Nice info. Just harvested my first bagged lion’s mane and while it rests will be attempting to propagate some of the remaining mycelium. A bit quicker than using spores, but I have never tried it from a fruited source. No great loss if it fails, as already got my money’s worth, but if successful, (almost) free product in perpetuity. Relocating to the PNW in an area well know for fungi, and would be awesome to have a few jars of inoculant ready to go.

I am looking to get in contact with Lion’s Mane grower’s in USA that would be able to produce 5000KG dry powder per year. Does anyone know someone I could get in contact with?

How can you determine the dosage content for the product? Fresh? Dried? Dried and ground?

Hello everyone. As of today – October 5, 2021, I can only see a Clinical trial being conducted (still planning) to 40 participants for H. ericaneus for USA. I’ve been looking for more but I hope many can provide here. Also, do you have a copy of Mendel Friedman’s study? I tried purchasing it in Wiley for 48-hour view but the document was blank. Please let me know to those who can share.

Farmer here with a few acres of undisturbed mixed hardwoods- mostly oak (red, pin, white/river), hickory and beech. I’d seen lion’s mane on one still living beech tree a few years ago so I know it can/does grow here- but it was just a lone “mane” so it’s not prevalent. I’d like to add more but (I’m not cutting down my beech trees!) . Any reason why I can’t just add spores to exist fallen trees, deadwood etc? And if it grows on a living tree why not try that?

On fallen and deadwood trees after 1 month there can already be other spores from enviroment.