Why Farmers and Gardeners Need Fear

Fear can be harnessed as a weapon against destructive pests.

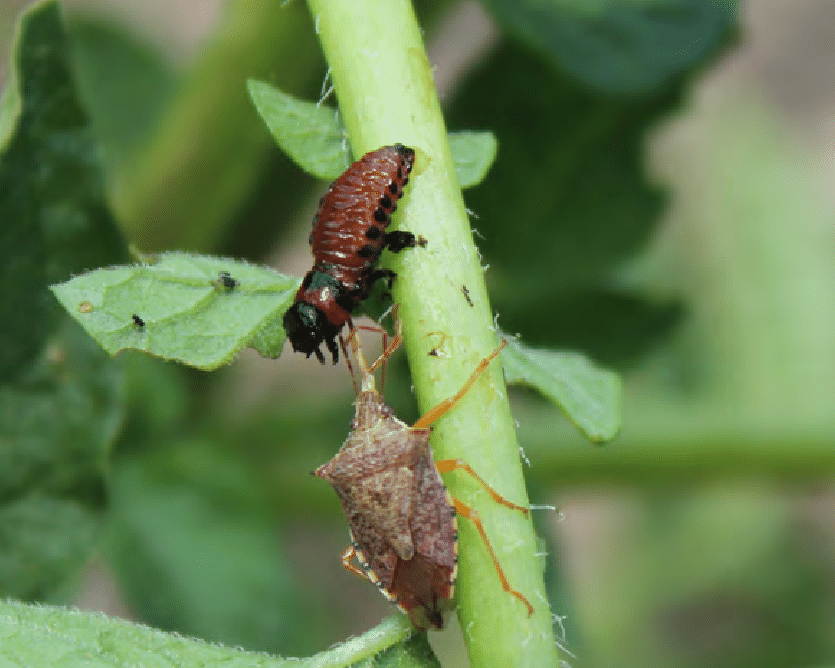

A lady-beetle larva consuming an aphid. Sanyay Acharya / Wikimedia Commons

No offense, but Franklin D. Roosevelt should maybe bug off with his assertion that “…the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” because fear is good for gardeners and farmers. According to entomologists Nicholas Aflitto and Jennifer Thaler of the Cornell University-based New York State Integrated Pest Management Program (NYSPIM), it can be harnessed as a weapon against destructive pests. Turns out it’s possible to scare harmful insects out of gardens and crop fields.

Ascribing human feelings to bugs may be a stretch, but if something makes the critters run away and hide, it seems fair, not to mention simple, to call that fear instead of “a consistent generalized avoidance response in reaction to certain stimuli” or some such thing. After all, it took biologists a few hundred years to establish that various animals from elephants to birds and turtles really and truly play, and for no other reason than to have fun. Perhaps one day we’ll figure out that invertebrates have emotional lives, too. I suppose that might raise ethical issues around pest control, but let’s not go there just yet.

Dr. Jennifer Thaler and Nick Aflitto say that “…convincing evidence suggests that the apparent risk of predation alone can reduce damage to plants by pests.” The researchers noted how pests, for example aphids, reacted when a predator such as a seven-spotted lady beetle came on the scene. They then compared this behavior to the way the pests responded to the mere odor of its nemesis and found that roughly the same number of pests dropped off the crops and hid in the soil. With aphids, between 40 and 60 percent generally bail out, depending on aphid species and host plant.

On the surface, this may not sound all that important. I mean, the pests only jumped off the plants – they weren’t killed. Apparently, it has a real impact on the survival rate and reproductive success of harmful insects when they have to continually stop feeding and head for cover. In a NYSIPM bulletin authored by Thaler and Aflitto, they explain that “As a pest shifts its energy from feeding and reproduction to hiding or dropping off of plants, it becomes less able to function or even survive.” Similar results were found in the case of Colorado potato beetles, which are just as terrified by the spined soldier bug as they are of its body odor.

A spined soldier bug consuming a CPB larva. Courtesy of Nicholas Afflito / Cornell University

If the chemical smell-alike of predatory insect BO can be cheaply made, this would be another gizmo in the Integrated Pest Management, or IPM, toolbox. IPM is not the same as growing organically, but it does stress non-chemical methods because they are usually just as effective as, and nearly always cheaper than, synthetic chemicals. It’s a win-win strategy for gardeners and farmers: IPM saves them money on pest management, and fewer toxins get released into our air, water and soil.

With IPM, there’s a kind of hierarchy of preferred methods. First on the list are cultural methods, such as keeping diseased potato vines out of your compost, and removing crop residue after harvest. Mechanical controls include staking tomatoes to minimize disease, and fencing to exclude deer and rabbits. Biological controls are things like having parasitoid wasps or predacious insects shipped to you from garden-supply firms to release into the garden or greenhouse. “Bug BO” also falls into this category. Non-toxic and/ or natural chemicals are next; an example would be Bacillus thuringiensis or Bt, a bacteria-derived natural toxin that is very specific in the pests that is can affect. Last, and ideally least, would be conventional pesticides.

Thaler and Aflitto say that we’re not quite to the point of being able to spray Eau de Mantis on the garden, but they are optimistic that growers will in the not-too-distant future have options available “to create a ‘scary environment’ for pests that reduces colonization, reproduction, and plant damage.”

For more information on a broad range of pests and recommendations for their control, visit the NYSIPM website at https://nysipm.cornell.edu/