Notes from the Field: Nerding-Out on Farm Tech

In this series, farmers will share what they are testing and trying.

Peppers, eggplants, tomatoes and cucumbers being trellised in late June at Tree Gate Farm.

Courtesy of Dean Koyanagi / Cornell Small Farms Program

Our farm here in Ithaca is approximately 40 acres of hilly glacial sediment made up of: 14 acres of woods, 18 for field crops, 2 for orchard, 4 for support and buildings, and 2 of permanent raised beds with wide grass paths between plots. Four 20’ x 48’ high tunnels are moved over the vegetable plots to keep the soil healthy and to manage a multi-year rotation cycle. In a small 15’ x 20’ hoop house protected to the north, we begin starting seedlings in February on heat mats; in May we begin setting out ginger, tomatoes, etc. in hoop houses. This year, our last frost was in mid-June.

Throughout the early season, temperature-related hazards pose threats at both the high and low ends of the mercury. While overnight temperatures get dangerously low for some plants, sunny days can bake a plant in a closed high tunnel. Knowing these swings in temperatures can be as critical as knowing when your walk-in cooler stops working in August when full of greens, or the root cellar door blows open when full of winter produce. Having a remote temperature reading (with alarms at certain set points, if possible) throughout the day can save a lot of time and mental uncertainty and distraction running back and forth to check as the sun comes up or clouds clear.

We’ve used several in-tunnel “rugged” outdoor thermometers, a sensor based on a tiny circuit board WiFi card, called an “Imp,” and have read about the range of commercial greenhouse sensors/controllers/waters ($$$). I even started to purchase components based on a design I found on Farm Hack that seemed like it was within my limited programming skills to wire and customize with a personalized alarm interface. But being in the middle of planting season and hearing of a local Ithaca company making a weather resistant WiFi/LoRaWAN (with a simple phone app) that requires very little configuration, and I could just drop it off in a tunnel had me intrigued. I ordered two Zynect “Thermote” temperature sensors for $89/each. While that would seem like a lot for an ordinary wall thermometer, here’s why I think is was a worthwhile farm expense:

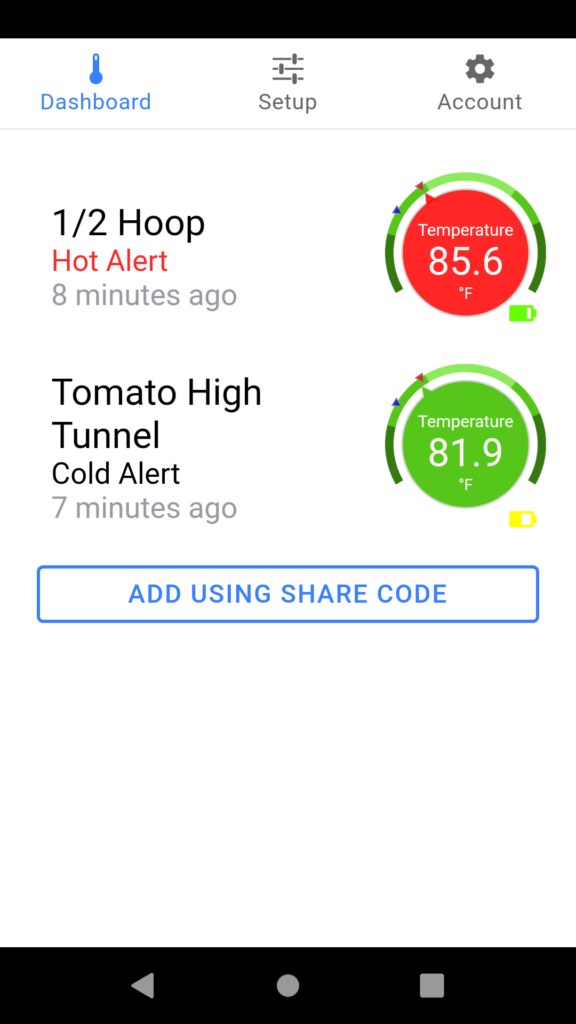

Zynect sensors app on an Android phone with the dashboard view showing a high temperature alert for one tunnel and a second sensor still below the alert temperature.

Courtesy of Dean Koyanagi / Cornell Small Farms Program

The cost of losing a crop is far more expensive. Waking up in the middle of the night wondering if you closed up the tunnel before a cold snap can be stressful. Being woken up in the morning by your partner informing you that you killed all of their favorite types of seedlings because you were supposed to close the tunnels … that’s a whole other plane of expense.

The Thermote is a sturdy plastic water-resistant case, that looks a lot like the ruggedized box I bought for my smartphone, only this one has a tail. The case protects the Zynect Thermote’s electronics and its temperature probe is at the end of a three-foot rubber cord. This allows you to place the actual sensor in a hot or cold spot (like in the freezer) with the electronics on the outside, where they’re less likely to get damaged. Knowing where you should place the sensor takes some thought and consideration. Where does the sun’s movements cause more overheating in your high tunnel during the day? Or, where does cold air sink and settle in a cooler? Those questions are more complex, and will be unique to your situation and use, but it’s pretty easy to place the sensor near a plant’s sensitive blossoms that are going to be the most impacted by high heat, or where cold air is blowing into your high tunnel. At one point we placed the Thermote in a metal box to keep it dry in the early spring, but it was too sunny, and the box became a little mini-oven as soon as the sun had cleared the treeline.

The Thermote’s setup is advertised at one minute, and you can review their setup instructions to see that it is indeed possible. First you pair the Thermote with your computer via bluetooth, then sign it in to your Wifi or nearby LorWAN antenna (they sell one for those who want to host a community antenna). Due to my phone’s clunky bluetooth pairing, it took me more like 15 minutes to get one of the sensors talking to the Zynect app properly. Depending on a given user’s techy-prowess, it may be prudent to factor in some extra time. Start by making sure you have a decent Android or iOS device, loaded with the Zynect app, that has Bluetooth to set up the sensor; as that’s not optional. For the second sensor, I thought I’d try connecting to a LoRaWAN antenna I know is nearby. For whatever reason, I was unable to connect to that tower, even after wandering around on the farm to see if it was impacted by indoor/outdoor, high ground, trees between me and the tower…but I never got the LoRaWAN to work. But since the WiFi connected easily to our outdoor antenna I didn’t spend more time on it.

The Zynect App interface is simple with easy to set alerts and you can share access to the data with as many others on your farm as you want. They just have to download the app, and you send them a link to access your sensor’s data. If you’re a data geek like me, you might have some occasion to want to see your data on your computer…and the app allows you to email a data file to yourself with a month, week, day or hours’s worth of temperature recordings. But the text alerts are what we’re most appreciative of right now.

I am planning to share some additional farm-tech field notes in future Quarterlies. What would you like to hear about? I have some notes queued up on the electrification of farm equipment, so maybe I’ll start there.

Additional Resources:

Farm Hack tool designs: https://farmhack.org/tools

Information about LoRaWAN: https://www.thethingsnetwork.org/

Zyntect sensors: https://zynect.com/

Editor’s Note: If you are interested in writing a “Notes from the Field” article, email the Small Farms Quarterly’s managing editor, Kacey Deamer, at kacey.deamer@cornell.edu.