Odor Is More Than a Nuisance

Affordable biofilters can keep your farmyard odor in check.

by Jason P. Oliver

The importance of good neighbor relations and the issue of odor

Foul odors can lead to criticism of a livestock farm and impede the good neighbor relations that are essential to a sustainable production. Due to changes in farm practice and manure handling, and to the encroachment of urban areas into regions traditionally dominated by agriculture, foul odor complaints are on the rise for farms of all sizes. Odor issues are complex due to their subjective nature, dependency on air dispersion patterns, and the complexity of odor itself.

Many different odorous compounds acting independently and together can trigger a human response when detected by the nose. Farm odors are typically mixtures of many odorous compounds at various concentrations. For example, a single dairy may emit more than 100 odorous compounds, while a swine farm may generate up to 500. Farm odors are not simply a nuisance or cause of complaint either since they contain hydrogen sulfide and ammonia gases. These gases are hazardous to farmers, their workers, and livestock at elevated levels, and can create acid deposition and eutrophication problems in the local environment.

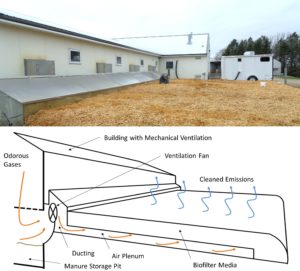

Figure 1: Photo and generalized schematic of a biofilter designed to simultaneously treat barn ventilation fans and manure pit emissions from a pig nursery barn in MN. The performance of this biofilter was continuously monitored by the author (seen on the biofilter) using the

instrument trailer in the background. (Photo by J. P. Oliver, Cornell)

Livestock farms of all scales produce odor

Foul farm odors can be directly emitted by any farm animal, though most are from the microbial breakdown of organic matter, particularly under anaerobic (lack of oxygen) conditions. Thus, farm odor generation is typically associated with barns, poorly managed composts and feed storages, silage mounds, and manure storage and treatment facilities. While land application of manure can generate significant odor, emission rates decrease rapidly after spreading, with immediate incorporation of manure into the soil mitigating most foul smells. So though manure spreading is highly visible to the public, the more persistent farmyard sources of odor typically create the greatest potential for issues.

Biofilters offer a low cost way to mitigate many farmstead odors

Biofilters (Figure 1) are simple odor mitigation technologies that use a pile of mulch, wood chips, compost, or other porous, organic media as an air filter. As an odorous air is forced through the biofilter, microbes living on the media breakdown the odorous chemicals to harmless products, essentially de-odorizing the air stream. Biofilters are not a new technology. Developed for wastewater treatment plant odor in the 1920s, they were used on German farms in the 1960s, and have been applied to U.S. livestock operations since the 1990s. When properly designed, constructed, operated and maintained, biofilters are capable of removing more than 90% of odor, hydrogen sulfide and ammonia, even at the very large swine facilities found in the upper mid-western states. While the adoption of biofilters by small farms has been slow, similar benefits are achievable.

Figure 2: A retrieved wood chip used as biofilter media showing diverse microbial biofilms. (Photo by J. S. Schilling, UMN)

How do biofilters work?

Biofilters are applicable to many different style farms and farm effluents due to the flexibility and adaptability of the microbes that underpin their function. Bacteria and fungi (and other microbes) in a biofilter assemble on biofilter media surfaces in growths called biofilms (Figure 2). By growing into airspaces in the media, biofilms increase surface area and improve capture of odorous gases as they are forced past. Once captured, competent bacteria and fungi breakdown the odorous gases for energy and nutrients. The media provides the microbes with carbon, and over time microbial growth will degrade the media into enriched compost that can be land applied. High microbial diversity present in these biofilms enables biofilters to treat hundreds of different odorous compounds at the same time and be adaptable to different farm effluents.

For an odorous air to be treatable, it first must be contained so blowers/fans can push it through a biofilter. Therefore, biofilters are best suited for the odorous air from barn ventilation fans, manure collection pits and treatment buildings, the shed where your manure chute loads your spreader wagon, buildings used for composting, even the exhaust fans of a food processing room. There are guidelines on how to select and size blowers/fans and media beds to ensure a biofilter will properly treat your farm’s odor – see the Resource Spotlight.

Simple biofilters can be constructed easily and at low-cost by farmers. Once you have selected your blower/fan and have calculated the size biofilter you need, all that is left is to build the ducting and air plenum to get your odorous air to and through the biofilter media, and install the media. I’ve seen working farmer-designs constructed using readily available materials such as pallets, plywood, bird netting, cement blocks, or wire mesh with free piles of wood chips and mulch used as media (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A Biofilter ducting constructed from treated plywood. The ducting lid is on hinges to allow access to barn ventilation and manure pit fans. B Framing of biofilter ducting made from scrap lumber. C Base of the ducting showing where odorous air enters the plenum air space under the media made from pallets. D Close-up of an excavated section of the pallet plenum, showing the bird netting used to support the woodchip mulch biofilter media. (Photo by J. P. Oliver, Cornell)

Once constructed, key to operating a biofilter is preventing compaction and managing moisture content of the media bed. If biofilter media is too compact or degraded, the blower/fan will not be able to move air through the media and the media will need to be replenished. Well-managed woodchip and mulch media can last over 3 years. Over-watering can also lead to air flow issues and create the same anaerobic conditions that generate odor rather than mitigate it. Watering too little, however, will desiccate media and reduce microbial activity. Ideally water content should be kept at 40-60% wet basis, and with a little trial and error can be maintained easily with a sprinkler. Some designs use roofs and cement sides for easier management of moisture content and media replacement.

Is a biofilter worth it?

Though biofilters have been only slowly adopted by small farms in the U.S. (and usually only in response to an odor complaint), I encourage you to think proactively about odor and how biofilters may fit into your farm system or future upgrade. So, while you might not have manure storage now, you may in the future as authorities push for better timed manure applications to improve nutrient management and protection of surface waters. And remember, foul odors are not good for you, your employees, your livestock, your community, or the environment. A less stinky farm is therefore in everyone’s best interest, and is an important step toward your farm’s sustainability goals. Consider low-cost biofilters a tool that can help you reach those goals.

Jason Oliver is a microbiologist in the Department of Biological & Environmental Engineering with expertise in biofiltration and livestock environmental systems management. He can be reached at 607-227-7943 and jpo53@cornell.edu.

To learn more about livestock odor, biofilters and their construction, see the University of Minnesota Air Quality Extension Page and the Fact Sheet Series on biofilters at the Cornell Dairy Environmental Systems webpage.

The main source of ammonia air emissions comes from animal agriculture in the UK. The other sources are agriculture and NH-3-based fertilisers. Ammonia is likely released when slurry and manure are exposed to the air. Some vegetation types, such as heathlands or bogs, which survive partly because of naturally low soil nitrogen, might become out of balance due to ammonia emissions that cause a terrible odour. While biofilters are an effective way to treat the odour from animal farms, some best odour eliminators in the UK do not need substantial exhaust fans.

The insight into biofilter technology highlights a promising avenue for addressing the complex issue of farmyard odor potentially improving both environmental and social sustainability.

Hot Tub Repair in Pinecrest FL