Bio-Integrated Fly Farming – Excerpt

Permaculture designer and farmer Shawn Jadrnicek is a master at engaging free forces of nature to create sustainable food production systems. Jadrnicek’s groundbreaking insights go beyond the philosophical foundation of permaculture to create hardworking, energy-saving farm-scale designs.

Permaculture designer and farmer Shawn Jadrnicek is a master at engaging free forces of nature to create sustainable food production systems. Jadrnicek’s groundbreaking insights go beyond the philosophical foundation of permaculture to create hardworking, energy-saving farm-scale designs.

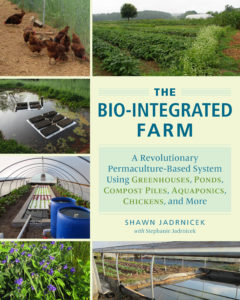

The following is an excerpt from his new book The Bio-Integrated Farm (March 2016) and is printed with permission from Chelsea Green Publishing

Bio-Integrated Fly Farming

During the last decade the farm and garden world has been abuzz about the black soldier fly. Native to North America, Hermetia illucens currently has a worldwide distribution in tropical and warm temperate regions. This small insect plays a large role in the decomposition of plants, animals, and feces by quickly composting waste and generating a high-protein feed for chickens and more.

Unlike common houseflies, adult black soldier flies aren’t found in kitchens, buildings, or picnic areas. Therefore, they aren’t vectors of disease or filth. In fact, black soldier fly larvae suppress housefly larvae by 95 to 100 percent by outcompeting them in the manure. Meanwhile, they reduce manure mass by about 50 percent over four hours when properly fed. The adult fly measures 3⁄4 inch long and looks similar to a wasp. You usually see the large flies hovering above compost piles or manure, depositing eggs nearby. The adults live for five to fifteen days, mating and reproducing. Their lack of functioning mouths indicates they live only to reproduce.

I first encountered black soldier fly larvae feeding on the fresh waste near the top of my home compost pile. The large larvae, about an inch long, had distinct segments all along their writhing bodies. The maggots were moving in a mass in a rotten watermelon placed on the compost. As they feed, they rid the waste of harmful bacteria and convert it into larval biomass. Unlike earthworms, black soldier fly larvae tolerate a wide variety of temperatures and moisture levels in waste. The larvae also consume waste faster than earthworms. And best of all, you can raise the larvae in special containers called digesters, from which the larvae will self-harvest into a bucket for collection as a feed for animals.

At the Clemson University Student Organic Farm (SOF), we use soldier fly digesters equipped with ramps to take advantage of the larvae’s natural tendency to vacate the waste before pupating. After they’ve fed voraciously on the waste, the larvae pull themselves up the ramp with a specialized mouthpart and fall into the bucket. Every one to five days, we collect the larvae and feed them to chickens, fish, prawns, or anything else in need of a high-quality protein and fat.

My first attempts at raising soldier fly larvae involved homemade digesters constructed from recycled worm bins. I have also worked with David Thornton, organic and biofuels project coordinator for Clemson University, to attach larger bins to greenhouses for season extension. Though the larvae consumed massive amounts of waste, our harvest was lacking. We lost many larvae to cracks and crevices, and some larvae never left the bin because of poorly designed ramps. Dr. Craig Sheppard at the University of Georgia developed a design for the most successful large larval rearing digesters. Constructed of concrete, the digesters are equipped with ramps on two sides sloped at angles between 35 and 40 degrees. A gutter is located at the end of each ramp. The larvae crawl off the ramp and into the gutter, then fall into a bucket. Commercial plastic digesters are now available and work well. They come in two styles, a large round digester with a diameter of 4 feet (ProtaPod) and a smaller rectangular digester (BioPod). Both have ramps ascending either side, directing larvae into a hole and bucket for collection.

Starting Your Own

Soldier Fly Digester

Like any other project, the hardest part of growing soldier fly larvae is just getting started. First, find a good location for your digester, an area protected from the sun and rain. Placing a lid directly on top of a digester prevents airflow and may cause temperatures to reach lethal levels. Situating a digester under an overhanging roof allows better ventilation and temperature control. Because of this, I like to locate digesters under a large roof overhang on the north side of a house or building.

Robert Olivier, founder and CEO of Prota Culture LLC, a company specializing in the bioconversion of waste through insect farming, recommends applying a layer of gravel on the bottom of digesters for drainage and aeration. He then covers the gravel with landscape fabric or a coir mat made from coconut husk. Larvae will eventually degrade fabric material, but the gravel will remain.

Several weeks after the last frost in your area, place a few pounds of waste material inside the digester to attract adults for egg laying. Native ranges for black soldier flies are climate zones 7 and higher, primarily in the southeast of the United States. In these areas adults usually find the waste material and lay eggs, so larvae appear naturally. However, if you live in a dry or cold climate, you may have to import larvae by mail order to get your brood going. Consult your local Extension office to determine if black soldier flies are present in your area. Check with local jurisdictions before importing a nonnative fly.

Once the female adult finds the waste, she lays a clutch of about five hundred eggs in a crevice near the waste. The eggs hatch in about four days in temperatures over 80°F. You should see larval activity within a week or two after placing food waste in your digester. Before larval activity strengthens, the waste material may smell. That’s why I recommend using only 2 to 4 pounds of waste during the larval seeding stage. Odors rarely occur once larval activity is dense, unless you overfeed the larvae. Foods such as cooked grains or moist chicken feed tend to be less smelly than other types of waste.

Moisture is another consideration when seeding the digester. Once the digester is active, you will add waste material daily, and the addition of new material maintains high moisture levels. But since you’re not adding new material daily during the seeding process, the waste material may become too dry. You may need to add moisture, similarly to watering a garden. Covering the waste material with a piece of shade cloth or muslin helps retain moisture and provide habitat for egg laying.

Houseflies may take up residence in the waste during the first few weeks until the soldier fly larvae eventually exclude them. Since housefly larvae have a lighter color, move faster, and don’t reach the same size as soldier fly larvae, you can identify them easily in the waste material. Research shows that flooding basins with 2.5 centimeters of water before adding chicken manure from caged hens situated over the basin gives nearly 100 percent control of houseflies. Soldier fly larvae tolerated the moist conditions, feeding on manure around the edges of the basin and eventually into the center. Since commercial digesters have drainage holes in the bottom, you would need a separate basin or tub to attract the soldier flies with flooded feed for this technique to work.