3. Cultivation Indoors vs. Outdoors

Outdoor Growing : Mimicking Nature

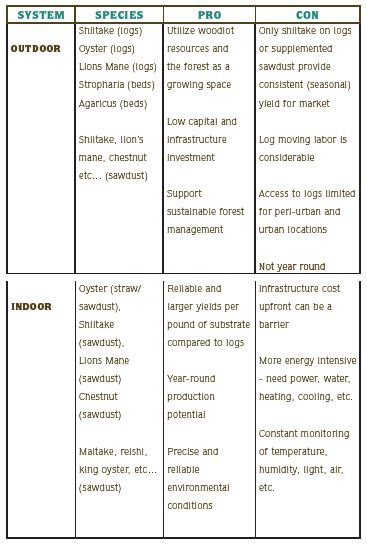

In many senses, growing mushrooms  outdoors is ideal because the forest (or any shady environment with good humidity and air flow) creates the ideal conditions for fruiting without the need for any climate control on the part of the farmer. Indeed, the forest is where the mushrooms we grow come from, so why not simply grow them there? For centuries, mushroom cultivators have been growing mushrooms on logs in the woods. Ken Mudge professor emeritus at Cornell University researched several species of forest-grown mushrooms for almost 15 years. He explored lion’s mane on totems, oyster on logs, wine cap stropharia on woodchips, and other minor species. In the end, he, along with most outdoor growers, focused on log-grown shiitake mushrooms, as they proved to have the most economic viability.

outdoors is ideal because the forest (or any shady environment with good humidity and air flow) creates the ideal conditions for fruiting without the need for any climate control on the part of the farmer. Indeed, the forest is where the mushrooms we grow come from, so why not simply grow them there? For centuries, mushroom cultivators have been growing mushrooms on logs in the woods. Ken Mudge professor emeritus at Cornell University researched several species of forest-grown mushrooms for almost 15 years. He explored lion’s mane on totems, oyster on logs, wine cap stropharia on woodchips, and other minor species. In the end, he, along with most outdoor growers, focused on log-grown shiitake mushrooms, as they proved to have the most economic viability.

the logs in water for 12-24 hours, which stimulates them to fruit. This method can be utilized to produce mushrooms quite reliably from around the first week in June through the middle to late part of October, at least in the climate of Central New York state. If you are further north, you can expect a shorter season, and further south, a longer one. The other species, while successful, fruit on their own time, and so are not good choices if the goal is to produce consistent yields for markets. What many commercial growers are now finding out is that supplemented sawdust blocks fruit amazingly well, on a reliable schedule during those similar months outdoors. As more businesses offer “ready-to-fruit” blocks for sale this option is becoming more feasible and economical for interested growers. In China, a large majority of commercial production is oriented around this system. Large scale industrial farms produce ready-to-fruit blocks and sell them to small scale farms. The farms are in ideal environments for production and, using minimal infrastructure, seasonally fruit the mushrooms. The mushrooms are primarily dried and then shipped to cities for sale. If this method is translated to the U.S., one key consideration is that the American consumer highly values fresh produce, so small-scale farms should be located close to the consumer.

As compared to indoor systems, the required infrastructure and start-up capital for outdoor mushrooms are low. Over their life cycle outdoor systems use considerably less energy as compared to indoor systems (other than in spawn production and inoculation). Outdoor systems can also support sound forest management practices, since we can directly link the materials (logs, stumps, woodchips, sawdust, etc.) to sustainable practices. However, outdoor mushroom production has its limits. For many growers, the market demands that more species than just shiitake be grown. In addition, those in urban and peri-urban areas may find it difficult to access logs or a shady woodlot. And the realities of a dynamic (and rapidly changing) climate mean that production cycles outdoors are unpredictable than indoors.

Indoor: Controlled Environment Growing

Once growers step out of the woods and into a contained space, they can grow year round and have very reliable and precise environmental conditions. Indoor systems offer a degree of buffering from the uncontrollable aspects of weather and climate that are a guarantee with outdoor production. Along with this change, growers have to start concerning themselves with monitoring and maintaining the ideal environment for fruiting.

Indoor farming systems are sometimes referred to as “controlled environment agriculture,” which includes other systems such as hydroponics, aquaponics, and greenhouse production. In contrast to systems used for greens and herbs, mushrooms can be produced in locations with minimal infrastructure and capital to start and sustain production. However, considerations and controls for temperature, humidity, light, and air flow need to be made. These can be addressed through relatively low-cost, off-the-shelf products, or one can get pretty “high tech” quickly if they so desire.

A big advantage of indoor production is that systems can be adapted to work in a wide range of abandoned and underutilized farm infrastructure including barns, outbuildings, high tunnels, and storage facilities. In an urban environment, basements, shipping containers, and warehouse spaces can be easily retrofitted for production. This positions mushroom production to be a system that is accessible to both rural and urban farms, as well as to farmers with limited capital and access to other resources.

Hybrid systems:

Farms may choose to focus solely on either outdoor or indoor production, or they may draw upon the benefits of both in a hybrid system. For instance, there are growers who bring shiitake logs indoors to extend the season, and in the same way some will bring blocks outdoors to fruit when the season naturally offers the right conditions. Farms will also sometimes keep shiitake production outdoors, as growing them indoors can occupy valuable space that can be allocated to species such as oysters, which get bugs in them when grown outside.