D. Business Planning

Before diving deeper into aspects of business planning for your shiitake enterprise, it’s worth taking a few minutes to brainstorm and answer the following questions:

WHY: Your objective. WHY do you want to take on this venture? WHY are you passionate or excited about this?

WHAT: Your product or service. WHAT will your business DO? WHAT will you sell? WHAT makes it special or interesting?

WHO: Your market. WHO are your customers? WHO wants what you are selling?

WHERE: Your location. WHERE will you operate/sell? WHERE are your customers?

WHEN: Your timeline. WHEN will you have this up and running? WHEN do you have to do things to make that happen?

HOW: Your finances. HOW will you cover the costs of start-up? HOW MUCH will it cost to make your product and to run your business? HOW MUCH will you need to sell to cover your expenses? HOW MUCH will you be able to pay yourself?

If the answers to these questions are “I don’t know,” then you should answer them before committing to production.

For some loans and assistance, you may need to write a full business plan. Resources to help can be found at: http://smallfarms.cornell.edu/2017/05/01/12-business-plans/

E. Budgeting and Cash Flow

In any farming enterprise, costs and profitability are highly variable, and depend on seasonal weather conditions and local markets, as well as the decisions of the farmer. Profits could greatly increase or decrease, depending on how the farmer chooses to purchase materials, spend their time, and work to optimize production efficiency.

A budget serves to compare your income with your costs, to summarize and project the overall track your business will take. For log-grown shiitake in particular, budgeting needs to be done over several years because the operation will usually phase into production with a number of logs. The following images and details are taken from excel spreadsheets that are available free for download at www.CornellMushrooms.org, where you can customize the figures to your situation. We have also printed these in the back of this publication.

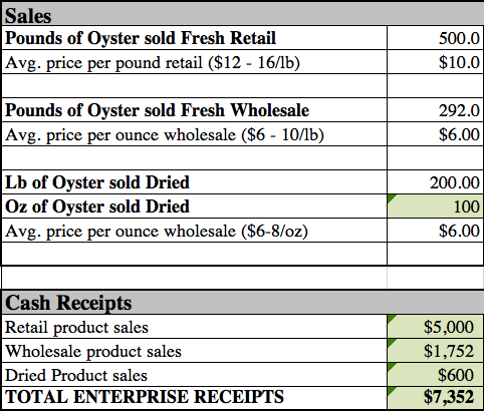

Let’s first examine an example of a 1,000 shitake log operation that is up and running at full capacity (usually by year 2 or 3). The production and expense figures are based on actual data collected from 2010 – 2012 from farmers producing log-grown shiitake.

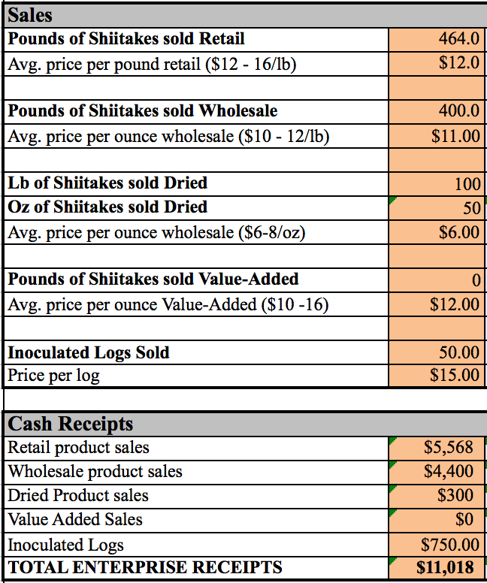

Sales can be divided up in a number of ways, depending on the goals of the farmer and local market demand.

Here, sales are pretty evenly divided between fresh sales both retail and wholesale, vs dried and value added sales.

Many growers also make income from selling pre-inoculated logs to customers interested in growing their own shiitake.

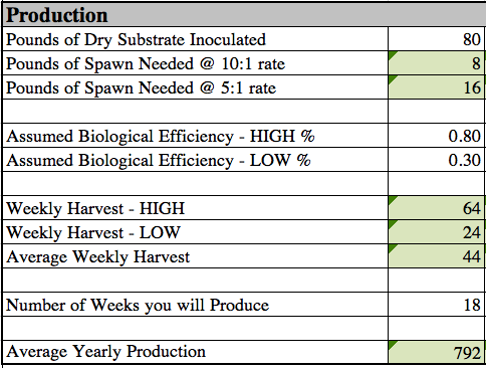

Here is an example of the production figures for indoor mushroom production. The production variables are different, where we look at the amount of dry material inoculated, along with the efficiency converting this material into mushrooms, known as Biological Efficiency. Beginner growers might achieve a lower efficiency around 30%, where as experienced growers can get between 80 – 100%.

Also important to note in this section are the number of weeks in production. Indoor mushroom cultivation allows the potential for year-round production, but for this example, we are assuming a seasonal production of 18 weeks during the warmer months in a Northeast US climate. It should also be noted that this is a relatively small scale operation, inoculating only 80 lbs (two straw bales) worth of material per week.

Here we see the grower chose to sell their mushrooms through a mix of retail and whole outlets, also drying some for a value-added product. The choices one makes for markets depend a lot on the price per pound that can be fetched. These numbers are conservative, as many specialty growers average $10 – 12 per pound across all channels, which will have big impact on the gross sales.

Taking a look at expenses, this budget accounts for the initial start up costs, many of which are a one-time expense as much of the control equipment and maintenance costs would be reduced or eliminated over time. Initial costs could also be much higher, depending on the space ones needs to develop as an indoor growing facility.

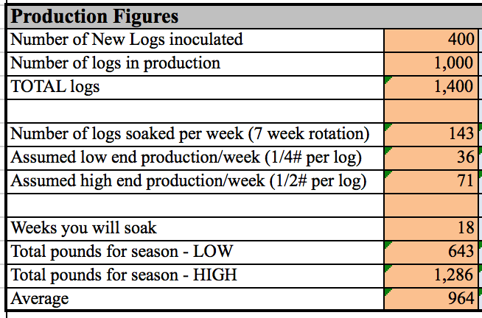

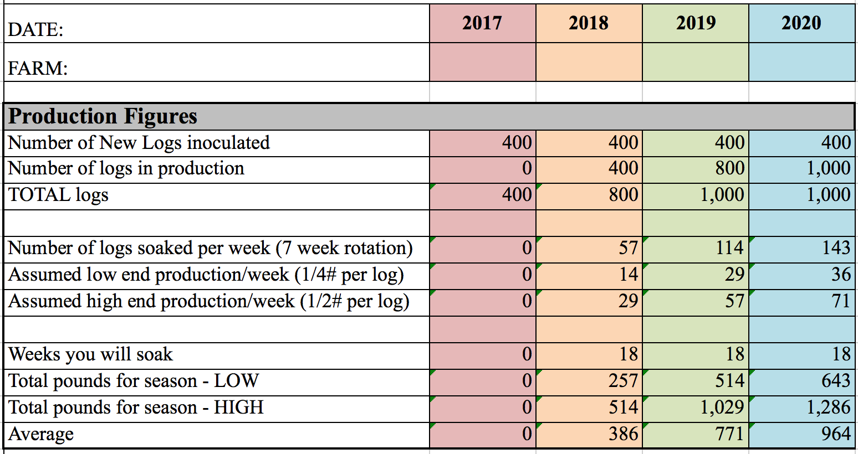

First, here are the projections for production. This is based on the number of logs in production, how many soakings occur, and the range of yields, which average ¼ - ½ pound of shiitake mushrooms per log, each time it is soaked.

This offers a yield that has a large range, so the further calculations are based on an average of producing 964 lbs.

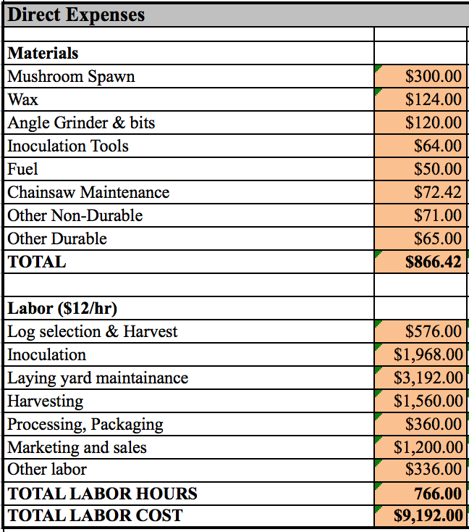

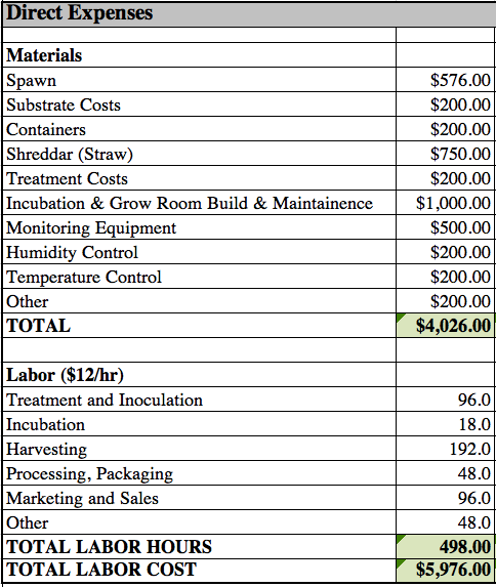

Next, we look at expenses, the most highly variable element in the budget, largely a result of the decisions a farmer makes. And, while sales can be adjusted to improve the amount coming in, the largest area of improvement for shiitake is in reducing expenses:

For example, the labor cost of inoculation is not often paid “in full” by most growers; many trade logs in exchange for volunteer help in the process. In addition, these labor figures were from beginning growers.

Over time, the rate of inoculation can improve greatly, as can the time spend in marketing and sales. We estimate that both of those categories could be cut by 50% with only modest improvements to the business, resulting in additional profit of almost $2,000.

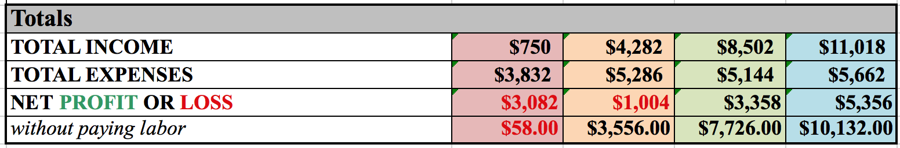

The two examples above are merely examples of all the variables that go into budgeting for an enterprise. We encourage growers to play with these variables on the excel spreadsheets, taking the exercise as an activity to help illuminate the areas where different decisions result in widely varying results. Ultimately, the more a grower is able to track their expenses and keep good records, the more accurate the budget can become.

Download the excel budget templates HERE.

Phasing into production

Perhaps even more important to understand is that mushroom farming has a bit of a different timeframe than some other crops. There is further distinction when considering outdoor log production versus indoor production. Namely, with logs a perennial crop is being maintained, since inoculated logs will remain productive for three seasons. Indoor substrates generally last for only 6 – 8 weeks, so could be considered more like an annual crop.

Regardless of the system, its generally recommended that growers start with a goal of the total number of logs or pounds of substrate he or she plans to maintain at full production. Then, working backward, the grower can make plans to expand production each year. Since outdoor shiitake production is most commonly phased in over multiple seasons, let’s look at an example of phasing into a 1000 log operation over for seasons:

The building of a productive system in this way carries other benefits. For one, labor starts out less intense, and grows as the number of logs does, along with grower experience and confidence. Sales also start out at a lower volume, giving the farmer time to develop markets. For these reasons, we encourage this phased entry over starting out trying to do 1,000 logs in the first season.

As with any farm business, this results in growers not getting paid (i.e. the enterprise isn’t profitable) for the first year. Still, achieving profitability in the third year is possible, and that is a relatively quick turnaround, especially when compared to many other crops.

For indoor systems, since the 6 – 12 month wait for logs from inoculation to fruiting is drastically reduced to 3 – 4 weeks, it is much easier to scale a system faster, even within just one production cycle.

Cash Flow Tracking cash flow is important to understand when you will have more or less money available for your enterprise. Often in farming, enterprises have high upfront costs and little money coming in until later in the season. Mushrooms are no exception.

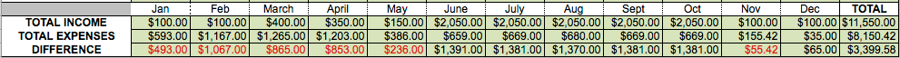

A cash flow example and blank worksheet are included in each of the enterprise budget templates. If the above numbers for a 1,000 log operation are plugged in, this is what it looks like:

As is often common with cash flow on farms, there is a clear deficit in the beginning of the season, when costs are high and sales are low. Seeing this helps make for better planning ahead of time.

While a grower can project these numbers and patterns to a reasonable degree, cash flow is most useful when accurate receipts and time records are kept, so the numbers become a true reflection of the reality.

F. Record Keeping

Your budgeting and cash flow documents will only be as good as the data you collect from one year to the next. Establishing a system that makes it easy to jot things down is crucial. Some farmers carry pocket notebooks, while others might take a note in their phone or keep a binder that lives in the barn and is easy for all workers to access. At a minimum collect the following:

- Date and number of new logs or materials inoculated

- Each Spring record a count of the number of active logs in the yard

- Date of soaking/number of logs soaked

- Date of harvest/number of pounds harvested from logs/bags/beds

- Lbs dried to Oz if dehydrating

- Sales (via invoicing)

- Material purchases (itemize “mushrooms” under Supplies in accounting)

With just the above items, you will be able to track your progress and determine where the money is coming and going. The real challenge is tracking hours. If writing them all down seems overly cumbersome, consider using a timer or stopwatch and getting average hours per week by just collecting a “snapshot” of data for one or two weeks of the season.

It’s worth at least estimating and noting time spent on the following tasks. Note the average time spent annually based on our 1,000 log scenario, as well as the typical time of year this is accomplished:

Jan - May

- Log Selection & Harvest (48 hours)

- Inoculation (164 hours)

- Marketing & Sales (50 hours)

- TOTAL = 272 hours

June - October

- Laying Yard Maintenance (112 hours)

- Harvesting (80 hours)

- Processing & Packaging (40 hours)

- Marketing & Sales (50 hours)

- Other (28 hours)

- TOTAL = 310

Tracking your hours gives you some time to reflect and compare your expenditure to the sample of farms above. Note that these hours spent are extrapolated from data based on a much smaller number of logs (100), and at a beginner level experience. There are several labor areas that could be significantly improved as growers optimize their systems. (see below)

ABSOLUTE NECESSITY #1: Tracking Expenses A farm that doesn’t track its expenses is not only unable to accurately report these to the IRS for tax purposes each year (a benefit to the farm), but also means that the farmer is running their enterprise on emotions rather than data. How can someone know if they are profitable if they don’t take the time to assess their enterprise, at least once a year.

At a bare minimum, farmers should save all receipts from farm-related purchases in a shoebox, and add them all up at the end of the year. Writing “mushrooms” or “feed” or “fuel” on the receipt at the time of purchase will help jog the memory. Ideally, this reconciliation occurs monthly or quarterly, so progress can be tracked, and problems avoided.

It helps to categorize expenses according to the IRS categories on a schedule F, to make the taxes easier at the end of the year:

- Admin

- Car & Truck

- Custom Hire

- Feed

- Fertilizer & Lime

- Fuel

- Insurance

- Labor Hired

- Rent or Lease – Equipment

- Repairs and Maintenance

- Seeds & Plants (Mushroom spawn goes here)

- Supplies

- Vet & Medical

For mushroom growing, the bulk of expenses will fall under “Supplies,” and it’s helpful to at least sub-categorize supplies for mushrooms versus other farm enterprises versus overall infrastructure. Set yourself up to at least be able to do this accounting work at the end of the season.

ABSOLUTE NECESSITY #2: Invoicing Sales Another essential piece of selling mushrooms is a system for tracking sales; sometimes known as invoicing. The basic system needs to be where you write (or type) the quantity sold, the price, and to whom, where one copy is given to the customer and the second you keep. The simplest way to do this is to create a half sheet invoice that can be torn in two; this way you duplicate the invoice, tear it in half, give one, and keep one for your records.

Receipt books with a carbon copy are perfectly fine for this. Many computer accounting programs can be set up to generate invoices and save one for you, automatically. Or, see Appendix C for a simple printable template you can copy and use.